Mammography for Breast Cancer Screening

An update of the evidence

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer among Canadian women. Current statistics show that one in nine women is expected to develop breast cancer during her lifetime and one in 29 will die of it (Canadian Cancer Society 2011). Research indicates that mortality rates of breast cancer have been steadily declining in past decades, especially in women under the age of 50 (Shen 2011). This has been attributed to many factors, including the widespread use of screening mammography. In the past, both Europe and North America have provided strong evidence in the form of meta-analyses that have supported the use of mammography in the reduction of breast cancer mortality (Kerlikowske 1995). These studies have suggested a wide range of impact from a reduction of 42% to an increase of 2% in mortality (Gøtzsche 2011).

However, more recent systematic reviews have shown that a substantial bias was present in the earlier studies. The differences in reported reductions in breast cancer mortality could not be explained by screening effectiveness and screening appeared to be ineffective (Gøtzsche 2011). This led to important changes in screening guidelines. In 2009, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released new recommendations advising against screening mammography for women before the age of 50. The science behind these recommendations has been challenged and notable controversy on the topic continues today among researchers and policy-makers (Hendrick 2011). Hendrick argues that the evidence made available to the USPSTF supports screening beginning at age 40, while the potential harms are minor (Hendrick 2011). Consequently, it is difficult for clinicians to advise their patients in an informed fashion. This paper reviews the most recent and strongest evidence available to help educate clinicians.

Current Canadian Guidelines

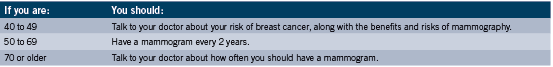

The recommendations on screening mammography provided by the Canadian government and the Canadian Cancer Society are equivalent. Provincial guidelines such as those provided by Cancer Care Ontario follow the same national guidelines. These guidelines are stratified by age. Women aged 40 to 49 are advised to talk to their doctors regarding their risk of breast cancer and the risks and benefits of mammography. Routine mammography for women of average risk is discouraged. Women aged 50 to 69 are advised to have a mammogram every two years. Women aged 70 or older are advised to talk to their doctors to determine how often to have a mammogram. Screening above the age of 74 is not recommended as the risks outweigh the possible benefits (Health Canada 2011).

For women between the ages of 30 and 69 at high risk of breast cancer, the chances of getting breast cancer are two to five times higher than in the general population. For this reason, guidelines recommend that women at high risk obtain yearly screening using both a mammogram and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). MRI has been shown to be significantly more sensitive than mammography and breast ultrasound in high-risk populations, especially in women with dense breast tissue (Le-Petross 2011). However, MRI is limited by its cost and availability and would lead to higher false positive rates.

The American Cancer Society considered there to be insufficient evidence to recommend for or against screening with MRI for women with a personal history of breast cancer, carcinoma in situ, atypical hyperplasia, and extremely dense breasts on mammography (Gemingnani 2011). Instead, they recommend screening MRI for women with an approximately 20% to 25% or greater lifetime risk of developing breast cancer (Saslow 2007).

In Canada, women are considered at high risk if they fall into one of the following categories:

• If they have already completed genetic testing for breast cancer and have received confirmation of a genetic mutation that increases breast cancer risk, such as BRCA1, BRCA2 or TP53.

• If they have not completed genetic testing themselves, but have a parent, sibling, or child with confirmation of a genetic mutation.

• If they have a family history that indicates hereditary breast cancer syndrome and who have a greater than or equal to 25% lifetime risk of breast cancer confirmed through genetic counselling.

• If they have received radiation therapy to the chest before 30 years of age as a treatment for another cancer or condition, such as Hodgkin’s disease (Health Canada 2011).

Pros and Cons of Mammography

Benefits

1) Detecting cancer (true positives). The sooner cancer is detected, the better the chances of survival. In other words, the earlier a cancer is found, the earlier it can be treated. Early detection usually implies that less treatment is required and a faster recovery time since the cancers that are detected sooner will likely be smaller and be less likely to have nodal involvement. Overall, this results in a reduction in morbidity and mortality for cancer patients, with the greatest benefit seen in high risk populations. The range of true positives for mammography in clinical trials is from 83% to 95% (Mushlin 1998).

2) Providing reassurance (true negatives). Many people prefer to have routine examinations to feel confident they are in good health. A negative mammogram can help reduce anxiety about suspicious breast lumps, or reduce fears that there is an underlying cancer that is going undetected. 3) Easily accessible and cost-effective. Mammograms currently play a central role in detecting breast cancers in the health care system. Mammograms do not massively tax health care resources. Mammograms may also exclude the need to obtain an alternative method of screening.

Risks

1) False positives. This occurs when the results of the mammogram suggest cancer even when none is present. This can result in unnecessary and painful invasive testing with biopsy and unnecessary psychological distress. These potential results are most applicable to women below the age of 50, where the false positive rates can be as high as 56% (Elmore 1998). In a small cohort of women, distress levels are heightened to worrying levels that may have long-term implications (Montgomery 2010).

2) False negatives. This is when cancer is not detected even though it is present. This can cause a false sense of reassurance and delay diagnosis and treatment.

3) Over-diagnosis and over-treatment. Certain cancers are not life-threatening, do not cause symptoms, and do not impact quality of life. Diagnosing and treating these cancers is unnecessary and there is no advantage in doing so. This may lead to needless testing, treatments, anxiety, and the consumption of resources. A meta-analysis reported the rate of over-diagnosis to be as high as 52% (Jorgensen 2009).

4) Increased exposure to radiation. X-rays used in mammography can have a negative influence on health and may increase the risk of cancer after cumulative exposure. However, it is thought that the improvements in technology make this risk minimal nowadays (Feig 1997).

The Evidence

The USPSTF recommends biennial screening for women aged 50 to 74 and advises against routine screening for women below the age of 50 or above the age of 74. On the basis of their systematic review, they also recommend against teaching self-breast exams (SBE) or utilizing clinical breast exams (CBE). The evidence shows that these recommendations help minimize the risks associated with mammography and that any additional testing, as with SBE or CBE do not confer benefits in addition to mammography (Nelson 2009). The USPSTF recommendation statement comes from an independent panel of public health experts and is based on an analytic framework that focuses on mortality as the primary outcome measure (Barton 2007). They believe there is an overwhelming consensus among advocacy groups to screen and that the discrepancy lies in the finer implementation of issues regarding what age groups should be screened and how often. Most international screening programs have adopted the same guidelines as the USPSTF (Gregory 2010).

Contrary to the most current USPSTF recommendations, some have argued that annual screening beginning at age 40 is justified (Hendrick 2011). One argument is that in making their decision, the USPSTF rejected all peer-reviewed studies that were not randomized controlled trials using mortality as the outcome measure. This meant the exclusion of a large number of studies which could have presented differing evidence. These authors also argue that annual screening for women 40 to 84 years old is estimated to convey a 39.6% mortality reduction, whereas biennial screening at ages 50 to 74 years is estimated to convey only a 23.2% mortality reduction. A recent retrospective study of the Cancer Registry Database in Missouri also showed similar results for the 40 to 49 age group, with a 19% increase in survival for those who had mammographically detected breast cancer versus those who had non-mammographically detected breast cancer (Shen 2011).

The issue of whether or not additional screening confers benefit is contested. In Europe, a large retrospective study showed that screening did not play a direct part in the reduction of breast cancer mortality (Autier 2011). The decrease in mortality was thought to reflect a combination of decreased use of menopausal hormone therapy and delayed diagnosis because of a decrease in utilization of mammography screening (Gemignani 2011). However, the issue that is perhaps more important is whether or not the magnitude of any benefit outweighs the potential harms and warrants mass screening for the general population. The absolute risk of developing breast cancer for women in their forties is low compared with other age groups (Gemignani 2011). The USPSTF estimated that it would require 1904 women of ages 40 to 49 years to save one life and concluded that the degree of harm in this age group outweighed the benefit (Hendrick 2011). This data is similar to the analyses done by the Cochrane Collaboration.

screening did not play a direct part in the reduction of breast cancer mortality (Autier 2011). The decrease in mortality was thought to reflect a combination of decreased use of menopausal hormone therapy and delayed diagnosis because of a decrease in utilization of mammography screening (Gemignani 2011). However, the issue that is perhaps more important is whether or not the magnitude of any benefit outweighs the potential harms and warrants mass screening for the general population. The absolute risk of developing breast cancer for women in their forties is low compared with other age groups (Gemignani 2011). The USPSTF estimated that it would require 1904 women of ages 40 to 49 years to save one life and concluded that the degree of harm in this age group outweighed the benefit (Hendrick 2011). This data is similar to the analyses done by the Cochrane Collaboration.

The authors concluded that screening is likely to reduce breast cancer mortality, but that the reduction is estimated at 15% or an absolute risk reduction of 0.05%. Screening led to 30% over-diagnosis and over-treatment or an absolute risk increase of 0.5%. This means that for every 2000 women who undergo mammography screenings during a 10 year period, one will have her life prolonged and 10 will be treated unnecessarily. In addition, more than 200 women will experience significant psychological distress for numerous months because of the false positive findings. Seen under this light, it is not clear whether mammography does more good than harm (Gøtzsche 2011).

Conclusion

The question of whether or not to screen for breast cancer with mammography is a difficult one to answer conclusively. The most educated answer for clinicians at this point in time may be “it depends.” Breast cancer causes significant morbidity and mortality and all advocacy groups recommend screening schedules in some form. However, some of the largest and most powerful research suggests that the benefit of mammography may be minimal and that the harm caused may outweigh any advantages (Gøtzsche 2011). There is agreement among clinicians that breast cancer screening has potential benefits and potential harms and the largest obstacle is determining how to appropriately guide patients using evidence-based recommendations.

It is imperative that clinicians stratify patients according to individual risk by taking a thorough history and using information such as patient age, age at menarche, child-bearing status, and breast density to minimize false-positives (Murphy 2010). If a patient has several risk factors or strong predictive risk factors, making the decision to screen becomes simpler. It is also of vital importance that clinicians educate their patients and communicate effectively the risks and benefits of screening mammography. To be able to do this, it is essential that clinicians have a thorough understanding of the most up-to-date research and statistics (Hirsch 2011). Finally, clinicians must have an understanding of the alternatives to mammography, including CBE, SBE, MRI, breast ultrasound, thermography, etc. Every screening test has its limitations, but they are constantly improving and some form of testing is key to err on the side of caution. The most appropriate screening strategy is still best determined for each individual patient. Further research is needed to clarify exactly under what circumstances mammography would be most appropriate.

References

Autier P, Boniol M, Gavin A, Vatten LJ. Breast cancer mortality in neighbouring European countries with different levels of screening but similar access to treatment: trend analysis of WHO mortality database. BMJ 2011;343:d4411.

Barton MB, Miller T, Wolff T, Petitti D, LeFevre M, Sawaya G, Yawn B, Guirguis-Blake J, Calonge N, Harris R, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. How to read the new recommendation statement: methods update from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:123–127.

Canadian Cancer Society. Canada-wide Breast Cancer Statistics. Available: http://www.cancer.ca/Canada-wide/ About%20cancer/ Cancer%20statistics/ Stats% 20at%20a% 20glance/ Breast%20cancer.aspx? sc_lang=en [accessed August 29, 2011].

Elmore JG, Barton MB, Moceri VM, Polk S, Arena PJ, Fletcher SW. Ten-year risk of false positive screening mammograms and clinical breast examinations. N Engl J Med 1998;338(16):1089–96.

Feig SA and Hendrick RE. Radiation risk from screening mammography of women aged 40-49 years. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1997;22:119–124.

Gemignani ML. Breast Cancer Screening: Why, When, and How Many? Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011; 54(1): 125-132.

Gøtzsche PC. Relation between breast cancer mortality and screening effectiveness: systematic review of the mammography trials. Danish Medical Bulletin. 2011 March; 58(3):A4246.

Gøtzsche PC and Nielsen M. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jan 19;(1):CD001877.

Gøtzsche PC and Olsen O. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD001877.

Gregory KD and Sawaya GF. Updated recommendations for breast cancer screening. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010; 22:498–505.

Health Canada. Mammography: When to have a Mammogram. Available: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hl-vs/iyh-vsv/med/mammog-eng.php [Accessed August 29, 2011].

Hendrick RE and Helvie MA. United States Preventive Services Task Force Screening Mammography Recommendations: Science Ignored. AJR. 2011 Feb; 196:W112-W116.

Hirsch B and Lyman GH. Breast Cancer Screening with Mammography. Curr Oncol Rep 2011; 13:63–70.

Jorgensen KJ and Gotzsche. Over diagnosis in publicly organized mammography screening programmes: systematic review of incidence trends. BMJ. 2009; 339:b2587.

Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, Sandrock C, Ernster VL. Efficacy of screening mammography. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;273(2):149-154.

Le-Petross HT and Shetty MK. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Breast Ultrasonography as an Adjunct to Mammographic Screening in High-Risk Patients. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. 2011; 32:266-272.

Montgomery M and McCrone SH. Psychological distress associated with the diagnostic phase for suspected breast cancer: systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2010; 66(11), 2372–2390.

Murphy, A.M. Mammography screening for breast cancer: a view from 2 worlds. JAMA. 2010; 303(2): 166-7.

Mushlin AI, Kouides RW, Shapiro DE. Estimating the accuracy of screening mammography: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(2):143–153.

Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151: 727–737, W237–W242.

Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan B, Nygren P, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: systematic evidence review update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Review Update No. 74. AHRQ Publication No. 10-05142-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009.

Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, Harms S, Leach MO, Lehman CD, Morris E, Pisano E, Schnall M, Sener S, Smith RA, Warner E, Yaffe M, Andrews KS, Russel CA, American Cancer Society Breast Cancer Advisory Group. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct tomammography.CA Cancer JClin. 2007;57:75–89.Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:185.

Shen N, Hammonds LS, Madsen D, Dale P. Mammography in 40-Year-Old Women: What Difference Does It Make? The Potential Impact of the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) Mammography Guidelines. Ann Surg Oncol 2011 Aug; DOI 10.1245/s10434-011-2009-4.

Tabar L, Vitak B, Chen HH, Yen MF, Duffy SW, Smith RA. Beyond randomized controlled trials: organized mammographic screening substantially reduces breast carcinoma mortality. Cancer. 2001;91:1724–31.