Infl ammatory Bowel Disease

A sampling of targeted integrative therapies

Infl ammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are chronic, relapsing-remitting infl ammatory diseases with several hallmarks of dysfunction, including a breakdown in intestinal barrier function and intestinal permeability, unchecked chronic infl ammation, and an exaggerated immune response characterized by imbalanced anti-infl ammatory and proinfl ammatory cytokines. Proinfl ammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha are increased with lowered anti-infl ammatory and regulatory cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-beta. When diagnosed with IBD later in life, aside from regular check-ups with gastroenterologists between procedures and to monitor effi cacy of pharmaceutical interventions, many adults have questions about their specifi c needs and are looking for additional support. However, many patients are reluctant to seek out integrative healthcare as they are concerned they will be encouraged not to take their medications which are helping to reduce their symptoms and provide quality of life. Naturopathic doctors have a unique opportunity to support patients with IBD by using the most appropriate treatments during diff erent stages of the disease process.

Supporting Intestinal Barrier Function and Intestinal Permeability

1.Prebiotic and Probiotic support Prebiotic supports (i.e. oligofructosaccharides and/or inulin found in chicory, wheat, onions, bananas) encourage growth of benefi cial bacteria and have the capability of skewing directional growth of probiotic strains which confer specifi c host benefi ts (Bouhnik 2004, Langlands 2004, Looijer-van Langen 2009). Some of these host benefi ts include providing energy sources for intestinal bacteria to ferment into short chain fatty acids (SCFA) (Looijer-van Langen 2009). Short chain fatty acids (SCFA’s) such as butyrate are a source of energy for colonocytes and can regenerate mucosa, as well as having the capacity to reduce infl ammation through enhancement of anti-infl ammatory cytokines such as IFN-gamma and NF-kB which are down-regulated in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis (Looijer-van Langen 2009). In a group of 19 patients with active UC (mild-moderate disease severity) administered inulin for 2 weeks in addition to the 3g/daily of mesalamine, a signifi cant reduction in calprotectin (a fecal infl ammatory marker increased in IBD) compared with the placebo control group was observed (Casellas 2007, Konikoff 2006). UC in general shows more signifi cant benefi t from prebiotic support compared with CD.

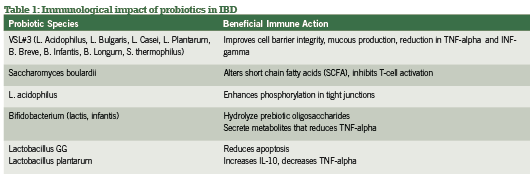

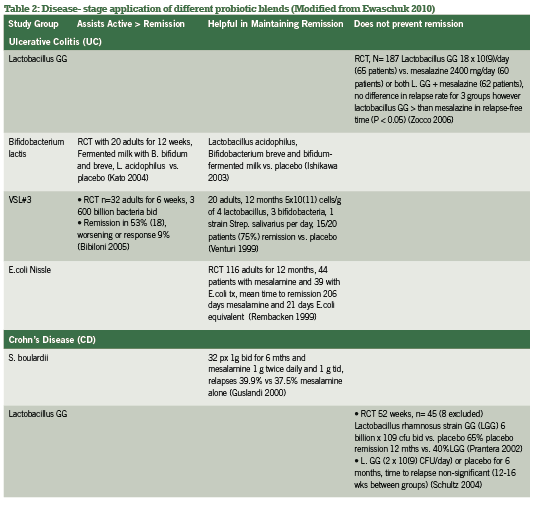

Probiotic support is widely considered a gold-standard intervention in both conventional and integrative medicine for both active and remission phases of IBD, with benefi ts of the most popular investigated strains summarized in Table 1. Current research has explored specifi c strains and their ability to infl uence active vs. remission phases of IBD, as summarized in Table 2. Of research produced to date, administering the proper probiotic strain(s) is crucial to seeing rapid improvements in bowel mucosa, stool quality and frequency, as well as reducing systemic infl ammation (Looijer-van Langen 2009). e probiotic VSL#3, which provides a high- dose milieu of bacteria, is more appropriate in IBD disease remission than is S. boulardii, which shows fantastic response for diarrhea-control and initiating remission (Ewaschuk 2010).

A recent meta-analysis comparing multiple studies and strains contrasted these conclusions for CD specifically, finding significance for E.coli and S. boulardii but not for lactobacillus strains (Rahimi 2008). Hence, screening for the proper strains by looking at disease activity and subjective symptomatology is the most useful strategy in selection appropriate probiotic blends for IBD management.

2. Amino Acid Supplementation Increased intestinal permeability can be predictive of how soon an individual relapses to active disease. IFN-gamma and TNF-a, central mediators of intestinal inflammatory diseases, induce intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction (MacDonald 1990, Wyatt 2004). L-glutamine, the major feeding source for enterocytes, has been suggested to have antioxidant potential by reducing nitrous oxide (NO) as well as restoring loose connections between tight junctions of colonocytes (Coeffier 2010, Grozswitz 2009). Animal-models of IBD induced via dextran sulfate sodium or acetic acid show promise with reduction of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-alpha and IL-8) and intestinal damage in the presence of L-glutamine consumption (Coeffier 2010). However, when used in human studies, glutamine supplementation does not show the same benefits in symptomatic reduction of disease activity through subjective scoring of the disease activity indices (CDAI) (Akobeng 2007, Den Hond 1999, Ockenga 2005). Study designs could use some improvements both in consistency of dosages administered as well as methodology of testing. Biopsies of inflamed gastrointestinal mucosa and measurements of cytokine levels are for the most part lacking in human trials post-glutamine consumption; perhaps it is in the microscopic changes of the intestinal barrier where the impact of L- glutamine supplementation will be observed (Coeffier 2005, Coeffier 2010)

Reducing Chronic Inflammation

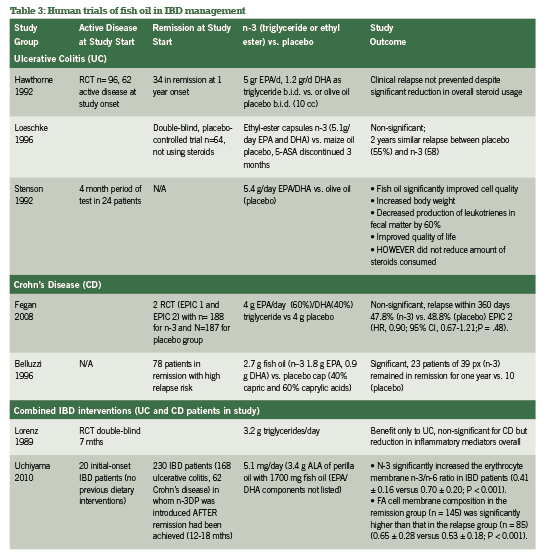

A. N-3 Fish oil The inflammation-reducing capacity of high-potency n-3 fish oils via the arachidonic acid pathways are well- publicized, acting as do current pharmaceutical supports for IBD including 5-ASA (Belluzzi 2000). While patients with IBD have steatorrhea and fat-soluble vitamin malabsorption, fish oil supplementation should be a top priority in integrative support of IBD (Hartman 2009). A selection of research groups in comparison of N-3, N-6 and N-9 oil usage for IBD across 10 years has been quickly summarized in Table 3 to further confirm the absolute necessity of n-3 fish oil for IBD support.

B. Curcuma longa or Curcumin Curcumin shows incredible promise from both preclinical models and recent human trials in IBD. It has demonstrated the ability to influence the arachidonic acid pathway and downregulate chemokine production (Arafa 2009, Goel 2007, Jagetia 2007). Neutrophil motility in IBD is correlated with disease severity with higher rates of neutrophil migration leading to reduced epithelial barrier function (Larmonier 2011); curcumin administration in murine models of IBD has demonstrated reduced neutrophil motility as well as reduced NF-kappaB as has led to further exploration in human IBD (Salh 2003).

Ex vivo¸biopsies from colonic mucosa and myofibroblasts from children and adults with active IBD exposed to curcumin in culture has demonstrated IL-10 production, reduction of IL-1B activity, and further reduction of cell signaling molecules in inflammatory pathways (Epstein 2009).

An RCT involving 89 patients with UC in remission were exposed to either 2 g/day of curcumin with sulfasalazine or placebo with sulfasalazine, with significant findings for delay of relapse in patients given curcumin (4.65%) as treatment compared with placebo (20.51%; p=0.040) (Hanai 2006). Further studies need to be completed, in addition to answering questions surrounding curcumins oral bioavailability (Marczylo 2007).

Oxidative stress

Reactive oxygen species and radical nitrogen metabolites accumulate rapidly during intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD, of which antioxidant support can be invaluable (Aghdassi 2003, Najafzadeh 2009). In addition to vitamin C, quercetin shows promise in animal models of IBD and has been used in combination with fish oil to restore glutathione concentration and to reduce COX-2 more significantly than with just fish oil alone (Camuesco 2006).

Dietary Support

As integrative healthcare providers, we concern ourselves with elimination of irritating proinflammatory foods such as dairy products (primarily cow’s milk), wheat gluten, peanuts, citrus fruits, fish and shellfish, synthetic and excessive sugar, and soy products. The “Western diet” high in animal meats, dairy, and sugars has been implicated in the increase in prevalence of both UC and CD in a comparison between 1990 and 2007 of reduced microbes in the intestines and food consumption (Asakura 2008).

Along the same vein, lactose intolerance and lactose malabsorption have a strong amount of research support with correlations to worsening IBD, especially CD compared with controls (Szilagyi 1998). Lactulose breath tests are often used to confirm this, however as most patients with IBD have imbalanced or higher than normal quantities of bowel flora, results prove to be inconsistent across many studies (Szilagyi 1998). Milk allergy and/or IgE antibodies to cow’s milk proteins are not often positive, which adds to the confusion where patients feel well avoiding dairy products but blood titres do not confirm the subjective improvements (Knoflach 1987, Mishkin 1997). Even if and when allergy results are positive and patients avoid offending foods for a period of time through elimination, intestinal permeability may still be increased as was demonstrated in a group of patients with IBD who avoided allergen exposure for six months yet still had high lactulose/mannitol ratios (Wyatt 1993). Intestinal permability can be an independent issue that is not easily solved with food avoidance.

In addition, replacement or substitution for these caloric losses in food avoidance is an issue as there is a need to nourish patients with IBD. Prednisone as an anti-inflammatory support in some patients with active IBD leaches calcium from the bones, and vitamin D is not only essential in directing calcium to the bones but to support proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-alpha suppression in IBD and in colorectal cancer prevention (Raman 2011). Among patients in remission from CD, 50% were shown to have low plasma concentrations of vitamin C (84%), copper (84%), niacin (77%), and zinc (65%) in addition to malabsorption of fat and fat-soluble vitamins (Filippi 2006). Exploring all options including screening for celiac disease, lactose intolerance, and multiple food allergies would be prudent rather than strictly eliminating foods without testing for such intolerances, thus taking each patient’s care as a unique situation despite general IBD trends.

Conclusion

Integrative healthcare providers play a unique supportive role in IBD. Recognizing the current disease state (active vs remission), the extent of inflammation, bowel flora status, and supporting processes of oxidative stress can improve quality of life for patients. Patients need the reassurance that they will not be in a competition or battle between their integrative healthcare provider and conventional supports (GI specialist, MD) but that we can provide improved quality of life by working as part of an integrative health care team.

References:

Aghdassi E, Wendland BE, Steinhart AH, Wolman SL, Jeejeebhoy K, Allard JP. Antioxidant vitamin supplementation in Crohn’s disease decreases oxidative stress: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98(2): 348-53.

Akobeng AK, Thomas AG. Enteral nutrition for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007: CD005984.

Arafa HM, Hemeida RA, El-Bahrawy AL, Hamada FM (2009). Prophylactic role of curcumin in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced ulcerative colitis murine model. Food Chem Toxicol ; 47(6):1311-7.

Asakura et al. Is there a link between food and intestinal microbes and the occurrence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis? Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008; 23: 1794–1801.

Belluzzi A, Boschi S, Brignola C, Munarini A, Cariani G, and Miglio F. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2000;71(suppl):339S–42S.

Belluzzi A, Brignola C, Campieri M, et al. Effect of an enteric-coated fish oil preparation on relapses in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 1557-616.

Bibiloni R, Fedorak RN, Tannock GW, Madsen KL, Gionchetti P, Campieri M, De SC, Sartor RB. VSL#3 probiotic-mixture induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1539–46.

Bouhnik Y, Raskine L, Simoneau G, et al. The capacity of nondigestible carbohydrates to simulate fecal bifidobacteria in healthy humans: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-response relation study. Am J Clin Nutr 2004, 80: 1658-1664.

Camuesco D, Galvez J, Nieto A, Comalada M, Rodriguez-Cabezas ME, Concha A, Xaus J, Zarzuelo A. Dietary olive oil supplemented with fish oil rich in EPA and DHA (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids, attenuates colonic inflammation in rats with DSS-induced colitis. J Nutr 2005; 135(4): 687-94.

Casellas F, Borruel N, Torrrejon A, et al. Oral oligofructose-enriched inulin supplementation in acute ulcerative colitis is well tolerated and associated with lowered faecal calprotectin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1061-1067.

Coeffier M, Marion-Letellier R, Dechelotte P. Potential for Amino Acids Supplementation During Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010; 16:518-524.

Coëffier M, Hecketsweiler B, Hecketsweiler P, Déchelotte P. Effect of glutamine on water and sodium absorption in human jejunum at baseline and during PGE-1 induced secretion. J Appl Physiol. 2005 Jun;98(6):2163-8.Epub 2005 Jan 20.

Den Hond E, Hiele M, Peeters M, et al. Effect of long-term oral glutamine supplements on small intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn’s disease. JPEN 1999;23:7-11.

Epstein J, Docena G, MacDonald TT, Sanderson IR. Curcumin suppresses p38 mitogenactivated protein kinase activation, reduces IL-1beta and matrix metalloproteinase-3 and enhances IL-10 in the mucosa of children and adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Nutr. 2010 Mar;103(6):824-32.

Ewaschuk JB and Dieleman LA . Prebiotics and probiotics in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(37): 5941-5950.

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Mittmann U, Bar-Meir S, D’Haens G, Bradette M, Cohen A, Dallaire C, Ponich TP, McDonald JW, Hébuterne X, Paré P, Klvana P, Niv Y, Ardizzone S,Alexeeva O, Rostom A, Kiudelis G, Spleiss J, Gilgen D, Vandervoort MK, Wong CJ, Zou GY, Donner A, Rutgeerts P. Omega-3 free fatty acids for the maintenance of remission in Crohn disease: the EPIC Randomized Controlled Trials. JAMA. 2008 Apr 9;299(14):1690-7.

Filippi J, Al-Jaouni R, Wiroth JB, Hebuterne X, and Schneider S. Nutritional Deficiencies in Patients With Crohn’s Disease in Remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2006;12:185Y19.

Goel A, Kunnumakkara AB, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin as “curecumin”: from kitchen to clinic. Biochem Pharmacol 2008;75:787-809.

Groschwitz KR and Hogan SP. Intestinal Barrier Function: Molecular Function and Disease Pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:3-20.

Guslandi M, Giollo P, Testoni P. A pilot trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003; 15:697-8.

Hanai H, Lida T, Takeuchi K, Watanabe F, Maruyama Y, Andoh A et al. Curcumin maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis: randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4(12): 1502-6.

Hartman C, Eliakim R, Shamir R. Nutritional status and nutritional therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(21): 2570-8.

Hasunuma O, Kurihara R, Iwasaki A, Arakawa Y. Randomized placebo-controlled trial assessing the effect of bifidobacteria-fermented milk on active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20: 1133-1141.

Hawthorne AB, Daneshmend TK, Hawkey CJ et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with fish oil supplementation: a prospective 12 month randomized controlled trial. Gut 1992, 22;922-8.

Ishikawa H, Akedo I, Umesaki Y, Tanaka R, Imaoka A, Otani T. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of bifidobacteria-fermented milk on ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Nutr 2003; 22(1): 56-63.

Jagetia GC and Aggarwal BB. “Spicing up” of the immune system by curcumin. J Clin Immunol. 2007;27: 19-35.

Kato K,Mizuno S,Umesaki Y ,Ishii Y ,SugitaniM,Imaoka A, Otsuka M, Knoflach P, Park BH, Cunningham R, et al. Serum antibodies to cows’ milk proteins in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 1987; 92:479-85.

Konikoff MR, Denson LA. Role of fecal calprotectin as a biomarker of intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammatory Bowel Dis 2006; 12: 524-34.

Langlands SJ, Hopkins MJ, Coleman N, et al. Prebiotic carbohydrates modify the mucosa associated microflora of the human large bowel. Gut 2004;53:1610-1616.

Larmonier CB, Midura-Kiela MT, Ramalingam R, Laubitz D, Janikashvili N, Larmonier N, Ghishan FK, Kiela PR. Modulation of neutrophil motility by curcumin: implications for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17(2) 503-15.

Loeschke K, Ueberschaer B, Pietsch A, Gruber E, Ewe K, Wiebecke B, Heldwein W, Lorenz R. n-3 fatty acids only delay early relapse of ulcerative colitis in remission. Dig Dis Sci 1996; 41: 2087-2094.

Looijer-van Langen MAC and Dieleman LA. Prebiotics in Chronic Intestinal Inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 15(3) 2009; 15: 454-462.

Lorenz R, Weber PC, Szimnau P, Heldwein W, Strasser T, Loeschke K. Supplementation with n-3 fatty acids from fish oil in chronic inflammatory bowel disease – a randomized, placebocontrolled, double-blind cross-over trial. J Intern Med Suppl 1989; 225-32.

MacDonald TT, Hutchings P, Choy MY, Murch S, Cooke A. Tumour necrosis factor- alpha and interferon-gamma production measured at the single cell level in normal and inflamed human intestine. Clin Exp Immunol 1990;81:301-5.

Marczylo TH, Verschoyle RD, Cooke DN, et al. Comparison of systemic availability of curcumin with that of curcumin formulated with phosphatidylcholine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2007;60:171-177.

Mishkin S. Dairy sensitivity, lactose malabsorption, and elimination diets in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 65:564-7.

Najafzadeh M, Reynolds PD, Baumgartner A, Anderson D. Flavonoids inhibit the genotoxicity of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and of the food mutagen 2-amino-3-methylimadazo[4,5- f]-quinoline (IQ) in lymphocytes from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Mutagenesis vol. 24 no. 5 pp. 405–411, 2009.

Ockenga J, Borchert K, Stuber E, et al. Glutamine-enriched total parenteral nutrition in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:1302–1309.

Prantera C, Scribano ML, Falasco G, Andreoli A, Luzi C. Ineffectiveness of probiotics in preventing recurrence after curative resection for Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial with Lactobacillus GG. Gut 2002; 51(3): 405-9.

Rahimi R, Nikfar S, Rahimi F, Elahi B, Derakshani S, Vafaie M, Abdollah M. A Meta-Analysis on the Efficacy of Probiotics for Maintenance of Remission and Prevention of Clinical and Endoscopic Relapse in Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53: 2524-253.

Raman M, Milestone AN, Walters JRF, Hart AL, and Ghosh S. Vitamin D and gastrointestinal disease: inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 200; 4(1): 49-62.

Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, Chalmers DM, Axon AT. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999; 354(9179): 635-9.

Salh B, Assi K, Templeman V, Parhar K, Owen D, Gomez-Munoz A, Jacobson K. Curcumin attenuates DNB-induced murine colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2003; 285(1): G235-43

Schultz M, Timmer A, Herfarth HH, Sartor RB, Vanderhoof JA, Rath HC. Lactobacillus GG in inducing and maintaining remission of Crohn’s disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2004 Mar 15;4:5.

Stenson WF, Cort D, Rodgers J et al. Dietary supplementation with fish oil in ulcerative colitis. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116: 609-14.

Szilagyi A. Altered colonic environment, a possible predisposition to colorectal cancer and colonic inflammatory bowel disease: Rationale of dietary manipulation with emphasis on disaccharides. Can J Gastroenterl 1998; 12(3): 133-146.

Uchiyama K, Nakamura M, Odahara S, Koido S, Katahira K, Shiraishi H, Ohkusa T, Fujise K, Tajiri H. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid diet therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Oct;16(10):1696-707.

Venturi A, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Johansson R, Zucconi E, Brigidi P, Matteuzzi D, Campieri M. Impact on the composition of the faecal fl ora by a new probiotic preparation: preliminary data on maintenance treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13: 1103-1108

Wyatt J, Vogelsang H, Hubl W, Waldhoer T, Lochs H. Intestinal permeability and the prediction of relapse in Crohn’s disease. Lancet 1993;341:1437-9.

Zocco MA, dal Verme LZ, Cremonini F, Piscaglia AC, Nista EC, Candelli M, Novi M, Rigante D, Cazzato IA, Ojetti V, Armuzzi A, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Efficacy of Lactobacillus GG in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006 Jun 1;23(11):1567-74.