Essential Hypertension

Management Considerations

Abstract

Over six million Canadians are currently affected by hypertension, a primary risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Elevated blood pressure accounts for approximately 13% of all deaths. The Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) provides annual recommendations for the assessment and management of hypertension in Canada. This article reviews the 2013 CHEP recommendations with a view to their application by integrative healthcare practitioners. For in-office diagnosis of hypertension, if blood pressure is elevated (SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg), it should be re-measured twice more in the same visit. The first measurement should be discarded and the latter two averaged to determine blood pressure. A focused physical exam and history assessing for target organ damage and cardiovascular risk should be performed; and a second visit should be conducted within a month to re-assess blood pressure. Special considerations exist for patients with diabetes and the very elderly. Target blood pressure in diabetics is SBP ≤130 mmHg and DBP ≤80 mmHg; while in patients ≥ 80 years of age it is SBP ≤150 mmHg. The role of integrative medicine in managing hypertension is discussed.

Introduction

Hypertension continues to be the primary risk factor for cardiovascular disease development, leading to myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke and kidney disease (Chobanian 2003). Worldwide, elevated blood pressure is also the leading risk factor for all cause mortality, accounting for 13% of all deaths (Robitaille 2012). The Framingham Heart Study data suggests that adults who are normotensive at 55 years of age have a 90% lifetime risk for developing hypertension (Vasan 2002), a statistic that warrants considerable emphasis on preventative cardiovascular efforts. The Canadian prevalence of hypertension is growing yearly, with six million diagnosed in 2008; hypertension is most prevalent in Atlantic Canada. Prevalence increases with age and in the female gender (after the sixth decade of life) (Robitaille 2012).

The Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP), operated and funded by Hypertension Canada, provides yearly updates to its recommendations for hypertension assessment and managementin Canada, a feat unmatched by any other country’s task force for hypertension or cardiovascular disease to date. An evidence-based approach is undertaken on an annual basis via systematic review of relevant clinical literature and recommendations are developed and disseminated by key independent stakeholders without external influence. The 2013 CHEP guidelines incorporate new recommendations for special populations suffering with hypertension as well as a greater emphasis on lifestyle and dietary considerations for management (Hackam 2013). These updates are relevant to integrative and conventional practices alike, and provide a more notably holistic approach to hypertension care. This paper will review current Canadian recommendations for blood pressure assessment and management with special attention to the integrative healthcare practitioner’s role in providing best patient care.

Hypertension diagnosis

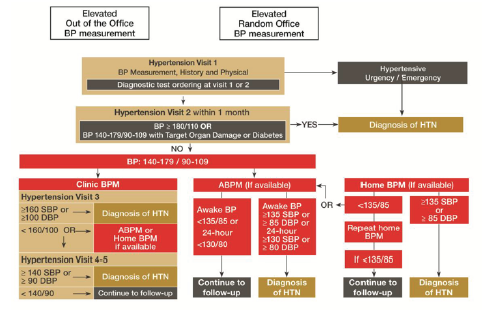

A diagnosis of elevated blood pressure, either in-office or by patient self-report, requires a specific workup based on certain criteria. In order to confirm a diagnosis hypertension, an algorithm for blood pressure measurement has been created

by CHEP 2013, as outlined in Figure 1.

of Patients with Hypertension (Hackam 2013)

Visit 1: Initial assessment

1. If the initial blood pressure denotes hypertensive urgency or emergency (defined in Table 1), an immediate diagnosis of hypertension is made and treatment is initiated.

2. If blood pressure is elevated (SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg):

a. Re-measure twice more in the same visit. The first measurement is discarded and the latter two averaged to determine visit 1 blood pressure.

b. Schedule follow-up within 1 month for assessment of hypertension.

c. Conduct a focused history and physical examination to assess cardiovascular disease risk and target organ damage (TOD) (defined in Table 2).

d. Assess for contributing exogenous factors and secondary causes of hypertension.

Visit 2: Follow-up assessment

1. If SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg with macrovascular target organ damage (TOD), diabetes mellitus (DM) or chronic kidney disease (CKD), diagnose hypertension.

2. If SBP ≥180 mmHg and/or DBP ≥110 mmHg without macrovascular TOD, DM or CKD, diagnose hypertension.

Visits 3-5: Follow-up assessment

1. If SBP ≥160 mmHg and/or DBP ≥100 mmHg averaged across first 3 visits, diagnose hypertension.

2. If SBP ≥140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥90 mmHg averaged across first 5 visits, diagnose hypertension.

3. If at the last visit the patient does not meet diagnostic criteria, and has no macrovascular TOD, reassess blood pressure yearly.

Table 1. Recognize Hypertensive Urgencies and Emergencies (Hackam 2013)

1. Asymptomatic diastole ≥ 130 mmHg

2. Elevations of blood pressure with:

• Hypertensive encephalopathy

• Acute aortic dissection

• Acute left ventricular failure

• Acute coronary syndrome

• Acute kidney injury

• Intracranial hemorrhage

• Acute ischemic stroke

• Eclampsia of pregnancy

Table 2. Target Organ Damage Examples (Hackam 2013)

1. Cerebrovascular Disease

a. Stroke: ischemia, transient ischemic attack, intracerebral hemorrhage, sub-arachnoid hemorrhage

b. Dementia: vascular, mixed vascular, Alzheimer’s

2. Hypertensive Retinopathy

3. Left Ventricular Dysfunction

4. Coronary Artery Disease

a. Myocardial infarction

b. Angina pectoris

c. Congestive heart failure

5. Renal Disease

a. Chronic kidney disease

b. Albuminuria

6. Peripheral Artery Disease

a. Intermittent claudication

In addition to these general guidelines for hypertension assessment and diagnosis, considerations must be made for certain special populations as defined by CHEP. These groups may not be best addressed by the general recommendations listed above due to physiological and/or clinical differences that affect blood pressure. When patients fall into these groups or subpopulations, it is important to adopt the specific guidelines relating to the implicated subpopulation in order to improve outcomes.

Hypertension and Diabetes

The prevalence of hypertension in diabetic patients is 63%, with 60-80% of diabetics dying from cardiovascular complications largely attributable to hypertension (Campbell 2009). Given the elevated risk of cardiovascular events in diabetics with comorbid hypertension, it is especially important for healthcare practitioners to be aware of their specific blood pressure targets and requirements. Integrative practitioners are specially poised to effectively address this group, given their expertise and ability to provide guidance on dietary and lifestyle modifications that help diminish this risk.

New 2013 recommendations for target blood pressure in diabetics are SBP ≤130 mmHg and DBP ≤80 mmHg (Hackam 2013). This target is based on evidence suggesting that more adverse events and less cardiovascular risk reduction is noted in intensive therapy where SBP targets were ≤120 mmHg vs. standard therapy using SBP targets ≤140 mmHg. Given that diabetics have well-known problems relating to hypo-perfusion, pushing blood pressure too low with treatments may also exacerbate events such as hypotension, syncope, bradycardia, hyperkalemia, angioedema and renal failure, some of which were noted when intensive hypotensive therapy was initiated in this population (ACCORD Study Group 2010).

Hypertension in the Elderly

The new recommendation for isolated systolic hypertension in the very elderly (age 80 years or older) is a target SBP ≤150 mmHg. Arterial thickening is known to occur with increasing age leading to a decrease in vessel elasticity. This physiological process results in systolic elevation with age, a finding that is now being recognized by CHEP guidelines in order to deter overmedication in the elderly population. No changes have been made to the diastolic blood pressure targets, which remain to be recommended ≤90 mmHg (Hackam 2013).

American guidelines note that these patients are more likely to have white coat hypertension and isolated systolic hypertension; in order to address these instances, practitioners should measure seated blood pressure and average two or more readings per visit (Pickering 2005). Additional strategies to circumvent white coat hypertension may include relaxation techniques applied at the discretion of the provider to aid measurement accuracy. Alternate methods for measurement, such as ambulatory and home BP measures, should also be considered.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests for Hypertensive Patients

Upon diagnosis of hypertension, the routine investigational laboratory panel should include the following:

1) Urinalysis*

2) Blood chemistry (potassium, sodium & creatinine)

3) Fasting blood glucose

4) Fasting lipid panel (total cholesterol, HDL, LDL & triglycerides)

5) 12-lead electrocardiogram

*Hypertensive patients with diabetes mellitus should also have urinary albumin assessed (Hackam 2013).

These laboratory measures aid in the investigation of target organ damage from longstanding untreated or inadequately controlled hypertension.

Hypertension treatment considerations

New CHEP guidelines are considerably more holistic in nature compared to previous Canadian guidelines (Daskalopoulou 2012) and currently adopted American guidelines from 2003 (Chobanian 2003). The primary focus of treatment continues to be on healthy behaviour management, including emphasis on physical exercise, weight reduction, alcohol consumption, dietary improvements, and stress management (Hackam 2013).

Pharmacological drug therapy guidelines have also been amended to address the greater shift towards lifestyle modification. The most notable of these changes include the delay of antihypertensive drug initiation for patients who do not have evidence of macrovascular target organ damage or other cardiovascular risk factors. In these otherwise healthy individuals, drug therapy is not recommended until the patient’s blood pressure indicates stage II hypertension, with an average SBP ≥160 mmHg or DBP ≥100 mmHg (Hackam 2013). American guidelines continue to recommend drug therapy initiation for stage 1 hypertensive patients, regardless of cardiovascular risk (Chobanian 2003). In the 2013 CHEP guidelines, stage I hypertension patients are to be recommended lifestyle modification instead.

The debate continues regarding which component of blood pressure is more concerning from the perspective of absolute cardiovascular risk. Recent reviews of evidence point to elevations in systolic pressure and pulse pressure as being most predictive of cardiovascular risk, whereas past epidemiological evidence has typically implicated diastolic elevation as a primary target for antihypertensive treatments (Pickering 2000, Strandberg 2003). Diastolic elevation has historically been regarded as more concerning due to the focus of large clinical trials on diastolic pressure; however more recent studies, including the Framingham Heart Study, confirm that systolic pressure accurately predicts true hypertension 96% of time compared to diastolic readings (Lloyd- Jones 1999). Both Canadian and American hypertension guidelines fail to explicitly distinguish isolated diastolic hypertension from isolated systolic hypertension in their recommendations for assessment, though practitioners should be aware that these do exist. From an evidence perspective, isolated systolic hypertension is a greater concern and requires more aggressive antihypertensive treatments compared to isolated diastolic hypertension. Both of these phenomena are more prevalent in younger patients, often males (Pickering 2000, Pickering 2005).

Lifestyle Recommendations for Hypertension

First line emphasis of treatment for stage 1 hypertension and pre-hypertension includes aerobic exercise and resistance training, neither of which are considered to adversely influence blood pressure. An effort to reduce the contribution of stress to blood pressure and to maintain a normal body weight is also emphasized; an area that integrative practitioners are especially poised to address effectively (Hackam 2013).

Dietary Recommendations for Hypertension

Specific dietary considerations of emphasis for hypertensive patients include sodium restriction <1500 mg for patients under 50 years of age, <1300 mg for those 51-70 years, and <1200 mg for those over 70 years. Alcohol intake should also be moderated in both pre-hypertensive and hypertensive patients, with recommendations for <14 standard weekly drinks in men and <9 standard weekly drinks in women (Hackam 2013). Both of these specific dietary guidelines should be made in conjunction with the recommendation to adhere to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet (Appel 2005; Hackam 2013). The DASH diet and Mediterranean diet continue to fare best at reducing absolute cardiovascular risk according to long-term and large-scale clinical trials (Appel 2005, Kokkinos 2005).

Role of Integrative Medicine

The role of an integrative medical practitioner in hypertension assessment and management is variable and diverse. Recent unpublished data reviewing naturopathic management of hypertension in a teaching clinic at the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine in North York, Ontario, suggests that a large proportion of practitioners fail to address their patients’ hypertension. The main reason for this trend was patient preference for a focus on other health needs given that their hypertension was being addressed by anti-hypertensive medications and followed by another health professional. Integrative practitioners are often presented with the clinical decision regarding the role played for hypertension management, specifically whether or not to adopt a primary care function in their patient’s hypertension care.

The above considerations are most relevant to a primary care approach to hypertension management, though aspects of these recommendations should be incorporated into any integrative practitioner’s care. Particular emphasis is warranted with respect to special populations of hypertensive patients, such as the elderly, those with diabetes, those with target organ damage and/ or other cardiovascular risk factors, as well as otherwise healthy individuals whose drug therapy may be safely delayed. Many primary and supportive therapies are available for hypertension management whether or not a patient’s blood pressure is medicated or controlled. Knowledge of primary practice guidelines, such as those positioned by CHEP 2013 in Canada (Hackam 2013) and NHBPEP 2003 in America (Chobanian 2003), is crucial to the appropriate care of patients who suffer from hypertension and to the ultimate success of integrative approaches for cardiovascular management.

Take Home Message for the Integrative Practitioner

• Measure blood pressure regularly in adult patients to assess cardiovascular risk

• Use a validated sphygmomanometer, choose an appropriate cuff size, and position the patient for accurate reading

• Understand CHEP recommendations for patients, including special populations with unique blood pressure targets

• Regularly assess for target organ damage.

References

ACCORD Study Group, Cushman W, Evans G, Byington R, Goff D, Grimm R et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010; 362(17): 1575–1585.

Appel L. Dietary Approaches to Prevent and Treat Hypertension: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2005; 47(2): 296–308.

Campbell N, Leiter L, Larochelle P, Tobe S, Chockalingam A, Ward R et al. Hypertension in diabetes: a call to action. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2009; 25(5): 299–302.

Chobanian A, Bakris G, Black H, Cushman W, Green L, Izzo J et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003; 42(6): 1206–1252.

Daskalopoulou S, Khan N, Quinn R, Ruzicka M, McKay D, Hackam D et al. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2010; 28(3): 270–287.

Hackam D et al. The 2013 Canadian Hypertension Education Program Recommendations for Blood Pressure Measurement, Diagnosis, Assessment of Risk, Prevention, and Treatment of Hypertension. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2013; 29(5): 528–542.

Kokkinos P, Panagiotakos D, Polychronopoulos E. Dietary influences on blood pressure: the effect of the Mediterranean diet on the prevalence of hypertension. Journal of clinical hypertension. 2005; 7(3): 165–70.

Lloyd-Jones D, Evans J, Larson M, O’Donnell C, Levy D. Differential Impact of Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Level on JNC-VI Staging. Hypertension. 1999; 34(3): 381–385.

Pickering T. Effects of Stress and Behavioral Interventions in hypertension – Headache and Hypertension: Something Old, Something New. Journal of clinical hypertension. 2010; 2(5): 345–347.

Pickering T. Recommendations for Blood Pressure Measurement in Humans and Experimental Animals: Part 1: Blood Pressure Measurement in Humans: A Statement for Professionals From the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005; 111(5): 697–716.

Robitaille C, Dai S, Waters C, Loukine L, Bancej C, Quach S et al. Diagnosed hypertension in Canada: incidence, prevalence and associated mortality. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2012; 184(1): E49–E56.

Strandberg T, Pitkala K. What is the most important component of blood pressure: systolic, diastolic or pulse pressure? Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 2003; 12(3): 293–297.

Vasan R, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Larson M, Kannel W, D’Agostino R, Levy D. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002; 287(8): 1003–1010.