Homeopathy

An introduction to application in pediatrics

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in pediatric primary care is common, with homeopathy being one of the most widely used CAM modalities in the world. In a recent survey done in the UK, the rate of homeopathic use in children amongst GPs is 22%, with most prescribing taking place for infants less than one year old with minor self-limiting conditions at a relatively low rate of approximately one per month. A smaller number of GPs report prescribing much more frequently (Ekins-Daukes 2005). In Germany, homeopathy is the most frequently used CAM treatment for childhood ailments, where nearly 50% of the homeopathic medicines are prescribed by medical doctors and Heilpraktiker, and used to treat a wide range of conditions with a greater rate of use for self limiting conditions (Du 2009). The publications on the use of CAM in pediatric primary care and oncology indicate that homeopathy plays a complimentary but largely unofficial role in pediatric oncology in Israel (Ben Arush 2006), Canada (Fernandez 1998), Italy (Steinsbekk 2006), and Netherlands (Grootenhuis 1998). In the US, it is estimated that over 900 000 children are administered homeopathic medicines on a yearly basis (Barnes 2008). In India, homeopathy is widely used in pediatric care, as it is incorporated as a system of primary care within the established medical system (Ghosh 2010).

Homeopathic remedies are potentized substances at a dilution level often greatly surpassing the Avogadro number. This naturaly gives rise to questions about the mechanism of action of homeopathic remedies. Despite much experimentation, the exact mechanism through which homeopathic remedies effect change remains elusive. Recent work has focused on the memory of water hypothesis in which properties of water are held to be influenced by the history of substances water has been in contact with (Chaplin 2007). Other work on the subject has focused on quantum interactions and entanglement of the remedies with the substances from which they are made, as well as quantum entanglement between the patient and practitioner (Molski 2010, Neuhouser 2001). Although no firm consensus has yet emerged, research into the question is gaining solid ground (Enserink 2010).

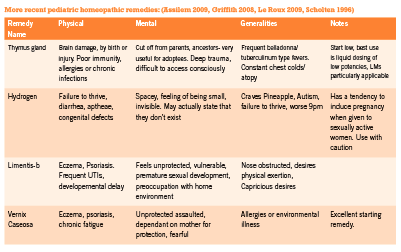

Most homeopathic remedies are made from natural ingredients (plants, minerals, or animals), yet numerous recent remedies have been created from a wider range of substances, such as colored light (Griffith 2008) and physiological tissues from the birth process (Assilem 2009). In addition, more recent work by Jan Scholten and the members of the Mumbai school in India have introduced classification of remedies into thematically oriented groups, and have offered deeper exploration into the unconscious levels of remedy pictures (Sankaran 2008). Their work has re-energized the field of homeopathy, widening the number of remedies that can be matched to childhood ailments.

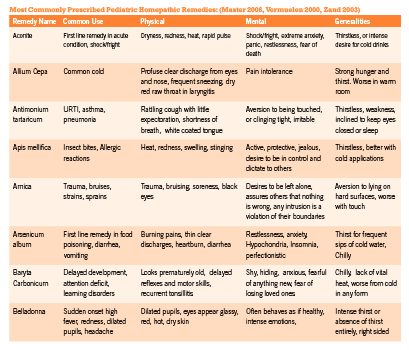

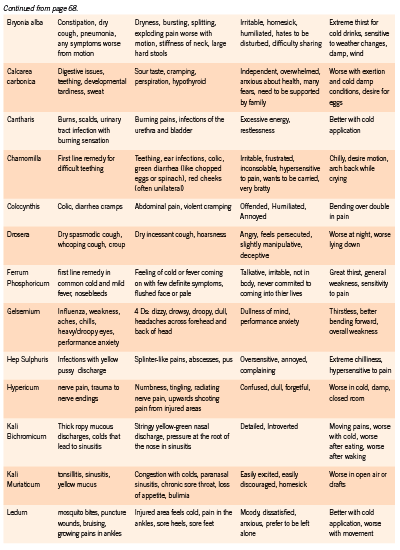

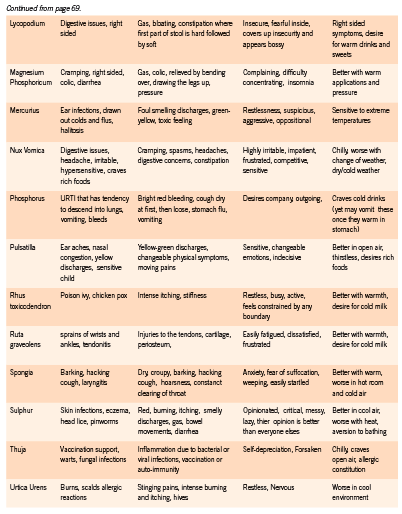

Homeopathic remedies are symptom specific. Prescribing in pediatric patients requires keen observational skills as well as a strong knowledge of materia medica. The choice of remedy must take into consideration general temperament of the child, the emotional responses to challenges that they are facing, as well as the unique details of the physical symptoms they are exhibiting or experiencing. This requires careful observation on the part of the parent and the physician since children are often unable to report the subtleties of their symptoms. In addition, observation of the parents and the social environment of the child may offer great clues to remedy selection (Master 2006).

Homeopathic remedies can be prescribed to children on an acute or constitutional basis. Constitutional prescribing is mostly indicated in chronic or recurrent conditions and is based on the child’s overall physical, emotional, and mental symptom picture. A constitutional remedy strengthens and stimulates the child’s vitality, improves physical and mental development and helps maintain their overall health over time. For acute presentations, symptom-specific prescribing based on the totality of the presentation at the time of intake is most commonly employed. A matching acute remedy will promptly releave the child’s symptoms and significantly increase rate of recovery.

Dosing strategies in children are similar to adult protocols. Although most books on pediatric dosing recommend low dose prescribing, for healthy children with strong vitality, dosing higher potencies of 200c, 1M, and 10M often show great results, as long as the remedy is a close similimum. It is generally prudent, however, to begin with lower potencies (such as 6c, 30c) and gradually move up to 200c, 1M and 10M if vitality of the child is vague, or if the remedy match is not entirely revealed. For children with chronic illneses and disabilities, higher potency remedies may provoke aggravations or worsening of the presenting symptoms. In such sensitive cases, liquid dosing and LM dosing are recommended.

The following protocol is designed to minimize aggravations in sensitive children, yet speed up progress of their condition considerably: Begin with 6c potency of the selected remedy diluted and succussed in alcohol and water. Administer 1-10 drops to the child and observe for a week. If no response, redose. If positive response results, redose only when you see child ceasing to improve. If progress comes to a plateau, dose more often until daily dosing. The typical progression of potencies in this protocol is 6c, 30c, LM-1, LM-2, and upwards (De Schepper 2004).

References:

Assilem, M. Matridonal Remedies of The Human Family: Gifts of the Mother. 2009. Idolatry. ink . USA. Pp. 60- 69.

Barnes P, Bloom B. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Chilren: United States 2007. National Health Statistics Reports. Number 12. Dec. 2008

Ben Arush MW, Geva H, Ofir R, Mashiach T, Uziel R, Dashkovsky Z. Prevalence and characteristics of complementary medicine used by pediatric cancer patients in a mixed western and middle-eastern population. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2006;28(3):141–146.

Boon, HS et al. Practice patterns of naturopathic physicians: results from a random survey of licensed practitioners in two US States. “javascript:AL_get(this,%20’jour’,%20’BMC%20 Complement%20Altern%20Med.’);”BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004 Oct 20; 4:14.

Fernandez CV, Stutzer CA, MacWilliam L, Fryer C. Alternative and complementary therapy use in pediatric oncology patients in British Columbia: prevalence and reasons for use and nonuse. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16(4):1279–1286

“http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=%22Chaplin%20 MF%22%5BAuthor%5D”Chaplin MF. The Memory of Water: an overview. “javascript:AL_ get(this,%20’jour’,%20’Homeopathy.’);”Homeopathy. 2007 Jul;96(3):143-50.

De Schepper, L. Achieving and maintaining the simillimum : strategic case management for successful homeopathic prescribing. 2004. Full of Life Publishing. Santa Fe, NM.

Du Y, Knopf H. Paediatric homoeopathy in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009 May;18(5):370-9

Ekins-Daukes S, Helms PJ, Taylor MW, Simpson CR, McLay JS. Paediatric homoeopathy in general practice: where, when and why? British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2005;59(6):743–749.

Enserink M, Newsmaker Interview: Luc Montagnier, French Nobelist Escapes “Intellectual Terror” to Pursue Radical Ideas in China. Science 24 December 2010: Vol. 330 no. 6012 p. 1732.

Fernandez CV, Stutzer CA, MacWilliam L, Fryer C. Alternative and complementary therapy use in pediatric oncology patients in British Columbia: prevalence and reasons for use and nonuse. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16(4):1279–1286 “http://www.ncbi.

nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=%22Ghosh%20AK%22%5BAuthor%5D”Ghosh AK. A short history of the development of homeopathy in India. “javascript:AL_get(this,%20’jour’,%20 ’Homeopathy.’);”Homeopathy. 2010 Apr;99(2):130-6.

Griffith, C. The New Materia Medica: Key Remedies for the Future of Homeopathy. 2008. Sterling. New York.

Grootenhuis MA, Last BF, de Graaf-Nijkerk JH, van der Wel M. Use of alternative treatment in pediatric oncology. Cancer Nursing. 1998;21(4):282–288.

Le Roux, P. Butterflies. 2009. Narayana. Kandern, Germany. Pp. 42-43, 95-99.

Master F. Clinical Observations of Children’s Remedies. 2006. 3rd edition. Lutra Services BV. Eidhoven, Netherlands

Milgrom, L.R. Patient-practitioner-remedy (PPR) entanglement. Part 5. Can homeopathic remedy reactions be outcomes of PPR entanglement? Homeopathy 93, 94-98 (2004). “http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?term=%22Molski%20M%22%5BAuthor%5D”Molski M. Quasi-quantum phenomena: the key to understanding homeopathy. “javascript:AL_ get(this,%20’jour’,%20’Homeopathy.’);”Homeopathy. 2010 Apr;99(2):104-12.

Neuhouser ML, Patterson RE, Schwartz SM, Hedderson MM, Bowen DJ, Standish LJ. Use of alternative medicine by children with cancer in Washington State. Preventive Medicine. 2001;33(5):347–354.

Sankaran, R. Structure, Experiences with the Mineral Kingdom: Vol 1. 2008. Mumbai, India : Homeopathic Medical Publishers.

Scholten, J. Homeopathy and the Elements. 1996. Stichting Alonnissos. Utrecht, Netherlands. Simpson N, Roman K. Complementary medicine use in children: extent and reasons. A population-based study. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(472):914–16.

Steinsbekk A, Bentzen N, Brien S. Why do parents take their children to homeopaths? An exploratory qualitative study. Forschende Komplementärmedizin. 2006;13(2):88–93.

Vermuelen F. Concordant Materia Medica. 2000. 3rd Edition. Emryss bv Publishers. Haarlem, Netherlands

Zand J, Rountree R, Walton R. Smart Medicine for Healthier Child. 2003. 2nd Edition. Penguin Group. NY.