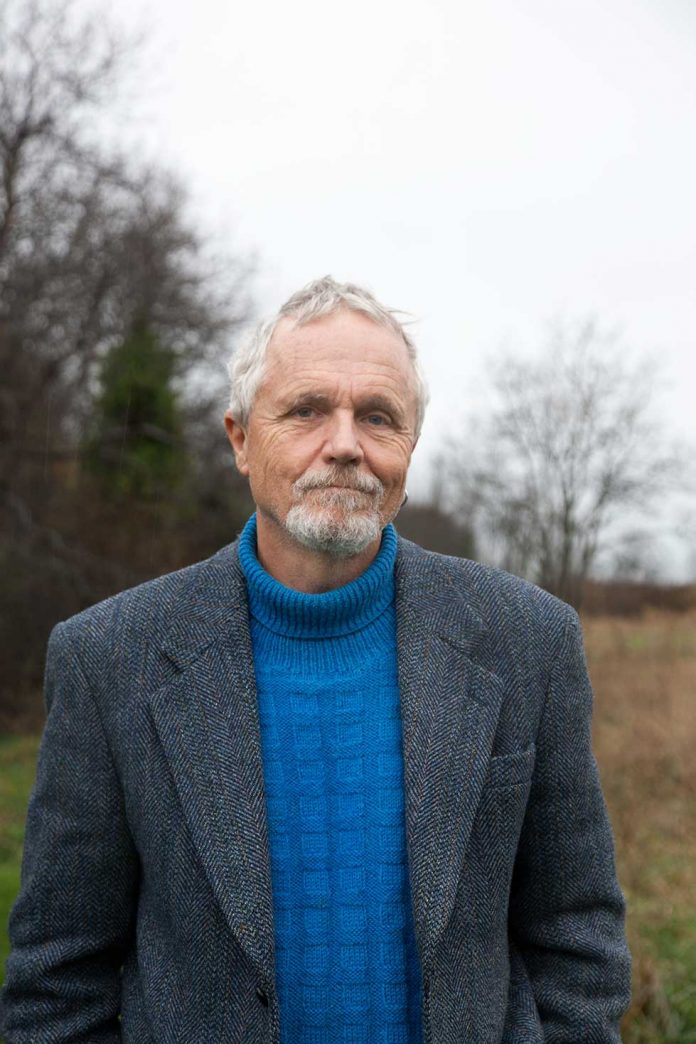

Genetic engineering researcher

Genetic engineering researcher has a change of heart – and mind

By Denise Deveau / Photographs by Angela Fama

For Dr. Thierry Vrain, it wasn’t an “aha” moment that ignited his passion for dispelling the genetically engineered (GE) myths. In fact, his journey was decades in the making.

Vrain was a respected researcher and proponent of GE for years. Now retired, he spent more than 20 years in biotechnology research with Agriculture Canada where his focus was on creating parasite-resistant potatoes, raspberries and strawberries, among other foods. However, Vrain’s post-retirement years led him to question the decades of work that he had put into agricultural research, and he’s ready and willing to talk about those doubts.

He admits that the early days of genetic engineering were exciting and dynamic for scientists like him. “Biotech was where the money was. It was easy to get funding, the technology was powerful, and the sky was the limit. You could do miracles working with DNA. I don’t recall ever having reservations about the work we were doing because we were learning to protect crops.”

Throughout his career he had often encountered the argument for organics, but he wanted to see facts supporting the claim. “Because I was a scientist, throughout my career organics seemed like a religious cult. There was no data or evidence anywhere to show it was any better than conventional methods. The only difference was the yields

were lower.”

Those numbers presented themselves in 2002, when he came across research papers from Europe on organic methods for growing food. “Seeing documents speaking a scientific language was a turning point for me. Because I’m a cell biologist, what was said in these studies about synthetic fertilizers damaging soil biodiversity made sense to me. There was a noticeable difference,” he says. “So I started becoming more and more interested and I realized that maybe genetic engineering was not all that good. Research from Europe, especially, is clearly showing some very serious problems.”

Part of that can be explained by conclusions that came of the Genome Project, which wrapped up in 2002. All of a sudden, the genome wasn’t at all what scientists thought it was, Vrain says.

The project determined that the human genome has 25,000 genes, but there are 100,000 proteins in the human body. “Everybody expected to see 100,000 genes. Instead, we learned that a gene can make more than one protein – and that’s very important, because proteins are the enzymes that work within cells that make life possible.”

The fact that a single gene sequence will create more than one protein translates into more than one activity. “When we alter that by genetic engineering, we don’t know what unexpected problems we could be creating,” he says. “Many studies now show that the protein you expect to see is either not there or has been truncated, altered or mutated.”

This counters 60 years of research in genetic engineering, Vrain notes. “GE is rooted in a very naïve understanding of genetics because it was based on a one gene/one protein hypothesis that was started when DNA was discovered in the late 1940s. Now we are realizing that introducing genes into a genome could introduce instability, creating proteins that should not be there. Right now we don’t know what

they do.”

The specific genetic engineering technology he speaks to is the one that allows plants to be sprayed with herbicide so that the weeds disappear and the plants continue to grow. The problem, however, is that the residue of that herbicide remains on the plant.

The consequences of this are far-reaching, since over 90 per cent of all those plants today are engineered to resist the Roundup herbicide, Vrain says. “When I was a grad student, Roundup was very new. It was non-toxic and biodegradable. We thought it was like water and as safe as aspirin.”

While those properties hold true, it’s the mode of action that has long-term consequences, he argues. By way of explanation, Roundup uses a chelating agent that captures metal ions. The chelation process was originally developed to clean up heavy metals in industrial wastewater, and was eventually used as a broad spectrum herbicide to kill weeds. “A chelating agent competes for metals so enzymes can be impaired, but many proteins need metal ions to function,” Vrain says.

As a result, genetically engineered foods contain residues of antibiotics. “While high or low residues of antibiotics won’t kill you instantly, over time it does damage flora for all animals, because there are 100 billion bacteria in each human’s gut,” he explains.

This is where European studies are showing some intriguing long-term outcomes. “They’re indicating definite organ damage on mice and rats after many months, which would mean many years for a human being,” he says. “There’s no denying that a large number of epidemic chronic diseases are on the rise in the last 20 years. If you put two and two together, there is a probable connection that herbicide residue and engineered crops could be contributing factors to that,” Vrain notes.

For those that argue the need for genetically engineered crops to feed the world, Vrain’s response is, “Industry will say after so many years and many trillions of meals, no one is harmed. But there is no evidence to provide [for] that. It’s empty.”

When not running his “super organic” farm on Vancouver Island, Vrain is increasingly being asked to present his views on genetic engineering, including an appearance on TED Talks. He has decided to join Dr. Shiv Chopra, a former Health Canada scientist who lost his job after going public with concerns about the potential human health risks associated with bovine growth hormone (rBGH), for his first-ever cross country speaking tour running through to February 2014. The “Genetically Engineered (GE) Foods and Human Health: A Cross-Canada Speaker’s Tour” is being held by the Society for a GE Free BC and Greenpeace Vancouver Local Group.

For Vrain, the writing should be on the wall for genetically engineered foods in North America. To date there has been legislation in Europe and other jurisdictions banning their use, yet North America continues to operate in a biotech bubble, he says. “There has never been any testing done in the U.S. or Canada by regulatory agencies, only by corporations, but most of the world has burst that bubble already.”

While Vrain doesn’t have a definitive answer on where the research will take them, “My conclusion would be that the future of agriculture is not genetic engineering.”