When patients want to get off their psychotropic medication(s)

Effective strategies for limiting withdrawal and destabilization

For over a decade I have focussed the majority of my clinical practice on the evaluation and treatment of mental health disorders. One of the most common requests I receive from patients is their desire to reduce or discontinue their psychotropic medications. It is entirely appropriate for patients to request this. eir psychotropic drugs might be doing more harm than good and creating many objectionable side e ects, which are limiting rather than enhancing quality of life (Moncrie 2006a). ey might want to see how they feel and function once their psychotropic drugs are reduced and/or discontinued. ey might also wish to be drug-free. When this request it made, I usually tell then something along the lines of:

“I need to see that you are stable for at least six-months before there is any consideration for reducing and/or discontinuing your psychotropic medication. By stability I mean: getting along well with family and friends; maintaining some type of regular work or employment, such as school, a volunteer position, or a career; and having no more disabling symptoms of your psychiatric disorder.”

This is usually well received since most patients prefer to work in a slow, methodical fashion, rather than becoming destabilized should this process be rushed.

Difficulties in Overcoming Pharmacological Dependence

Pharmacological dependence is an expected and biological adaptation of the body becoming long habituated to the presence of psychotropic drugs (O’Brien 2005). Since psychotropic drugs can induce unpredictable global reactions when used properly (Moncrieff 2006b, Moncrieff 2009), there are no reliable ways to predict how patients will overcome pharmacological dependence once their psychotropic drugs are tapered and eventually withdrawn. Every patient’s withdrawal process is unique as is their susceptibility to develop withdrawal side effects (Read 2005).

Discontinuation Reactions Following Cessation of Psychotropic Drugs

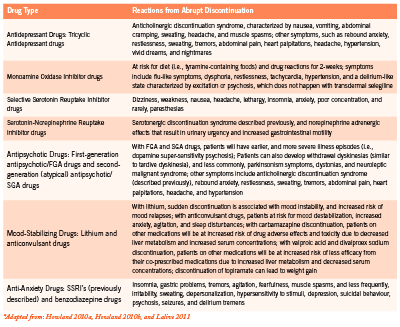

Some patients do fine and experience little withdrawal, while other patients have become so habituated and dependent on their psychotropic drugs that stopping them is paramount to disaster. While no ethical clinician would tell a patient to abruptly stop his/ her psychotropic drugs, it is important for clinicians to recognize discontinuation reactions from the common classes of psychotropic drugs (Table 1).

Tapering Patients off their Psychotropic Drugs

When it is appropriate for this to happen, I usually communicate in writing to the patient’s prescribing clinician (i.e., the general/ family practitioner or psychiatrist) that the patient is doing well and wants to try discontinuing one of his/her psychotropic drugs. If the prescribing clinician does not agree to any plan of psychotropic drug tapering, despite the patient’s wishes and noted stability, it is entirely appropriate for the patient and non-prescribing clinician to proceed with a tapering plan. In such a circumstance, it might be suitable to draft a waiver outlining all potential risks and benefits of psychotropic drug tapering with the patient. The waiver would have to clearly delineate that this is what the patient wants, and that the patient is willing to assume all risks (e.g., destabilization and hospitalization) associated with the tapering process.

Since there is a scarcity of clinical research pertaining to tapering patients off their psychotropic drugs, there are no clearly defined standards informing clinicians about the best and most appropriate method of tapering. Patients are just as likely to succeed in coming off their psychotropic drugs whether or not they have the support and endorsement from their prescribing clinicians (Darton 2005). The published data from one organization found that 53% of patients were successful in coming off their psychotropic drugs – even though this was either against their doctors’ advice or occurred without their doctors’ knowledge – compared to 44% that had their doctors’ approval (Read 2005).

The tapering plan should involve one drug at a time and should involve the drug with the longest elimination half-life first. Psychotropic drugs with longer elimination half-lives (i.e., more than 24 hours) are easier to taper from since their withdrawal reactions tend to be less severe than drugs with shorter elimination half-lives (i.e., 24 hours or less). Psychotropic drugs with short elimination half-lives can produce significant and quick withdrawal reactions. Considerations should be made to switch patients from psychotropic drugs with short elimination half-lives to drugs with longer elimination half-lives prior to tapering, as this will increase the chances of a positive experience and successful outcome. A psychotropic drug like vanlafaxine (has an elimination half-life of around five hours) can cause significant withdrawal and possible destabilization. A psychotropic drug like fluoxetine, on the other hand, can be used as a substitute for vanlafaxine, allowing for a more successful tapering plan since the elimination half-life of this drug is four to six days (Darton 2005).

Overall, the tapering plan needs to be very slow and gradual, which reduces the potential for relapse (Moncrieff 2006a). The patient should never be made to feel like a failure during this process since coming off of psychotropic drugs is very difficult due to the “physiological and psychological manifestations of the biological effects caused by the withdrawal of a regularly administered drug” (Moncrieff 2006a). For patients to successfully come of their psychotropic drugs they need to: (1) be well prepared and informed of the process; (2) have a positive attitude; (3) be mindful that they will experience strong emotions throughout tapering and possibly for months after; and (4) receive some type of regular psychological support (e.g., psychotherapy, art therapy, support groups, etc) during the tapering and perhaps beyond (Darton 2005, Hall 2007).

A good rule of thumb is for the tapering duration to be for the same length of time of previous psychotropic use (Hall 2007). For example, if a patient was on a psychotropic drug for six months, the tapering process should be six months. The only exception involves patients that have been on psychotropic drugs for five or more years. The tapering process for these patients should be approximately 18-24 months (Hall 2007).

One report suggests that for each unspecified tapering period, there should be a 10% reduction in dose, and that the psychotropic drug is reduced by subsequent 10% reductions until the patient is comfortably off his/her medication (Darton 2005). Another report suggests that the psychotropic drug is tapered down every two weeks, and that with each two-week tapering period, the dose is reduced by 10% (Hall 2007). If a patient, for example, begins the tapering process on a drug that is 400 mg once daily, than the dose to take for two weeks would be 360 mg. After two weeks, the dose would be further reduced by another 10% to 320 mg and so on. This process would continue until the psychotropic drug is fully discontinued. If, at any time during the tapering, the patient feels that the reduction is too marked or there are troublesome withdrawal reactions such as anxiety and sleep disturbances, the patient can remain on the previous tapered dose until he/she feels well enough to proceed.

Improving the Odds of a Successful Outcome

It is not uncommon for patients to experience problems even from small reductions in their psychotropic drugs. This is usually misattributed to a re-emergence of their underlying psychiatric disorder as opposed to problems related to psychotropic drug withdrawal (Moncrieff 2006a). When this happens, it is common for such patients to be shamed by family members, psychiatrists, and support workers into the notion that they cannot maintain their psychological health without depending on psychotropic drugs for the rest of their lives, thus forcing patients back onto long-term treatment (Moncrieff 2006a). Darton (2005) reported that patients with mental health issues are too often denied the chance to come off their medications, to take risks, and potentially make their own mistakes. If, on the other hand, family members are helpful, supportive, and encouraging, this will reduce risks associated from tapering off psychotropic drugs (Darton 2005).

chance to come off their medications, to take risks, and potentially make their own mistakes. If, on the other hand, family members are helpful, supportive, and encouraging, this will reduce risks associated from tapering off psychotropic drugs (Darton 2005).

Supporting the Tapering Process with Specific Natural Health Products

There are specific natural health products that I have found helpful when used during and after the tapering process to mitigate withdrawal, and prevent potential relapses, and possibly the need to resume previous psychotropic drugs. Melatonin is being formally studied to ascertain its benefits among schizophrenic patients withdrawing from long-term benzodiazepine use (Baandrup 2011). Previous reports have shown some efficacy in reducing benzodiazepine-withdrawal-associated sleep disruption (Dagan 1997, Peles 2007). Ideally, controlled- or prolongedrelease preparations should be used, with doses varying from 1-5 mg at bedtime. Sometimes it might be preferable to use quick release melatonin, as this might help patients that have difficulty falling asleep.

Niacinamide (nicotinamide) is sometimes very useful among patients withdrawing from benzodiazepines since it possess benzodiazepine-like effects (Prousky 2004). One case report demonstrated its clinical effectiveness in allowing a patient to remain clinically stable after tapering off clonazepam (Prousky 2004). With the approval of his psychiatrist, the patient weaned himself off clonazepam in two weeks while increasing his daily amounts of niacinamide until he was taking 2500 mg each day. When this report was published, the patient had been free of clonazepam for six months and had remained stable on only the niacinamide.

Niacinamide can also be given to reduce withdrawal symptoms when other psychotropic drugs are tapered since it generally “calms” the nervous system and does not possess any concerning drug interactions. Effective daily doses of niacinamide range from 1500-2500 mg. It is rarely necessary to go beyond 2500 mg since such doses can be associated with nausea and potentially vomiting. The mean elimination half-life in human subjects given 3000 mg of the vitamin was 5.9 ± 0.6 hours (Horsman 1993). Since it has a very short half-life, niacinamide must be administered several times throughout the day; otherwise, its therapeutic effects will be lessened.

Neurapas® balance is a unique herbal medicine that contains three potent psychoactive herbal extracts. Each film-coated tablet contains 60 mg of the dry extract of Hypericum perforatum, 28 mg of the dry extract of Valerian officinalis, and 32 mg of Passiflora incarnata. There have been approximately 10 company-sponsored clinical studies (i.e., two controlled and eight observational cohort studies) and two experience reports, which have demonstrated this herbal combination to be safe and effective for both depression and anxiety (Pasco Neurapas® CTD Documentation 2005a). Each of the individual herbal extracts has well known postulated mechanisms of action (Werneke 2006). As the tapering process continues, I generally have my patients increase Neurapas® balance to two pills three times daily. Unfortunately, the elimination half-live is not known for this preparation.

Rhodiola rosea extract is an important intervention since clinical trials have shown it to attenuate mild and moderate depression, generalized anxiety, and burnout/fatigue (Bystritsky 2008, Darbinyan 2007, Olsson 2009); common withdrawal symptoms that many patients experience during tapering. It specifically works by inhibiting enzymes involved in the degradation of monoamine neurotransmitters (i.e., serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine) and prevents the depletion of adrenal catecholamines following acute stress (No authors listed 2002). The therapeutic dose range is somewhere between 500-680 mg of a standardized extract containing 3% percent total rosavins and 1% salidrosides, in divided doses. I recommend that Rhodiola rosea extract is taken with food, as it can cause considerable nausea and possibly vomiting on an empty stomach.

There are numerous other natural health products that could potentially be used alongside psychotropic drugs during the tapering process. Clinicians trained in clinical nutrition and botanical medicine must use their own discretion during psychotropic drug tapering, while also mitigating any potential interactions, and using available pharmacokinetic information to guide appropriate dosing.

Conclusion Helping patients taper from their psychotropic drugs is complicated by many factors, including their stability, support system, and the length of time they have been on psychotropic drugs. This is also controversial since family doctors and psychiatrists often oppose tapering due to concerns of ongoing stability, and their beliefs that psychotropic drugs are required over the long-term. From my perspective, all mentally competent patients have the right to choose what they think is best, even if such beliefs are not held by the clinicians providing care. This paper should assist and empower clinicians to develop effective tapering strategies on behalf of their willing patients.

References

Baandrup L, Fagerlund B, Jennum P, et al. Prolonged-release melatonin versus placebo for benzodiazepine discontinuation in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial – the SMART trial protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:160.

Bystritsky A, Kerwin L, Feusner JD. A pilot study of Rhodiola rosea (Rhodax) for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:175-180.

Dagan Y, Zisapel N, Nof D, et al. Rapid reversal of tolerance to benzodiazepine hypnotics by treatment with oral melatonin: a case report. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1997;7:157-160.

Darbinyan V, Aslanyan G, Amroyan E, et al. Clinical trial of Rhodiola rosea L. extract SHR-5 in the treatment of mild to moderate depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:343-348.

Darton K. Making sense of coming off psychiatric drugs. London, UK. Mind Publications. 2005.

Hall W. Harm reduction guide to coming off psychiatric drugs. The Icarus Project and Freedom Center. September 2007. Retrieved from: www.theicarusproject.net/ downloads/ComingOffPsychDrugsHarmReductGuide1Edonline.pdf (December 12, 2011).

Horsman MR, Høyer M, Honess DJ. Nicotinamide pharmacokinetics in humans and mice: a comparative assessment and the implications for radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1993;27:131-139.

Howland RH. Potential adverse effects of discontinuing psychotropic drugs. Part 2: antidepressant drugs. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2010a;48(7):9-12.

Howland RH. Potential adverse effects of discontinuing psychotropic drugs. Part 3: antipsychotic, dopaminergic, and mood-stabilizing drugs. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2010b;48(8):11-14.

Lalive AL, Rudolph U, Lüscher C. Is there a way to curb benzodiazepine addiction? Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13277.

Moncrieff J. Why is it so difficult to stop psychiatric drug treatment? It may be nothing to do with the original problem. Med Hypotheses. 2006a;67:517-523.

Moncrieff J, Cohen D. Do antidepressants cure or create abnormal brain states? PLoS Med. 2006b;3(7):e240.

Moncrieff J, Cohen D. How do psychiatric drugs work? BMJ. 2009;338:1535-1537.

[No authors listed]. Rhodiola rosea. Monograph. Altern Med Rev. 2002;7:421-423. O’Brien CP. Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 (Suppl 2):28-33.

Olsson EM, von Schéele B, Panossian AG. A randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled, parallel-group study of the standardised extract shr-5 of the roots of Rhodiola rosea in the treatment of subjects with stress-related fatigue. Planta Med. 2009;75:105-112.

Pasco Neurapas® CTD Documentation. Module 2:2.7 Clinical Summary Neurapas® balance, film coated tablets. 2005a;1-165.

Pasco Neurapas® CTD Documentation. Module 2:2.5 Clinical Overview Neurapas® balance, film coated tablets. 2005b;1-39.

Peles E, Hetzroni T, Bar-Hamburger R, et al. Melatonin for perceived sleep disturbances associated with benzodiazepine withdrawal among patients in methadone maintenance treatment: a double-blind randomized clinical trial. Addiction. 2007;102:1947-1953.

Prousky J. Niacinamide’s potent role in alleviating anxiety with its benzodiazepinelike properties: a case report. J Orthomol Med. 2004;19:104-110.

Read J. Coping with coming off: mind’s research into the experiences of people trying to come off psychiatric drugs. London, UK. Mind Publications. 2005.

Werneke U, Turner T, Priebe S. Complementary medicines in psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:109-121.