NAFLD

Clinical application of betaine and L-carnitine

Introduction

Alarming trends have emerged for non alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). The diagnosis of NAFLD is associated with a higher all cause mortality than the general population. The prevalence of NAFLD has been estimated to be as high as 17-33% in certain countries. Furthermore, a subset (approximately 33%) of NAFLD patients develop non alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Increasing concerns have stemmed from the fact that 20-25% of NASH patients could develop severe cirrhosis (Raszeja-Wyszomirska 2008). Once cirrhosis occurs, detrimental effects follow, such as portal hypertension, esophageal varices, ascites, encephalopathy and hepatorenal syndrome (Rahn 2010). The most important factor to consider is the clinically silent nature of disease in its early phases, making effective preventative and therapeutic measures all the more essential.

Clinical Features and Management of Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Non alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) encompasses a comprehensive list of disorders with the hallmark of macrovesicular, hepatic steatosis, and associated pathology ranging from no inflammation to that of fibrosis and cirrhosis (Wedemeyer 2003). The pathogenesis of NAFLD includes insulin resistance, oxidative stress, dysfunctional apoptotic pathways and pro inflammatory cytokine elevations (Younossi 2008). The etiology of NAFLD and contributing factors include obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and hypertension. Specific metabolic risk factors worth noting are waist circumference >90cm for men and 80cm for women, impaired fasting glucose >6.1 mmol/L, triglycerides >1.7 mmol/L, HDL levels <1.3 mmol/L in women and 1.03 mmol/L in men and hypertension >135/80mmHg (Adams 2006).

NAFLD can be asymptomatic or produce non specific early symptoms, such as fatigue and dull upper abdominal pain. Late stage symptoms include but are not limited to nausea, weight loss, lack of libido, gastrointestinal bleeding and itching/swelling of the extremities (Schiff 2007, Wedro 2009). Signs such as jaundice and hepatomegaly may also be present. Laboratory findings for this condition consist of elevated liver function tests (ALT, AST and GGT). Although imaging such as ultrasound (less sensitive) and MRI can be utilized as diagnostics tools, the gold standard for NAFLD is liver biopsy and an exclusion of 20g/day of alcohol consumption (Adams 2006).

Widespread initial treatment for NAFLD consists of diet and exercise alone if NAFLD is mild, however, drug regimens are also utilized. Pharmacological intervention consists of medications, such as lipid regulators (Orlistat-lipase inhibitor that reduces fat absorption, Atorvastatin-statin), insulin regulators (biguanide- Metformin), thiazolidinediones (Pioglitazone, Rosiglitazone), antihypertensives (Telmisartan) and Ursodeoxycholic Acid (Musso 2010).

Natural Health Product Interventions for the Treatment of NAFLD

There are several contenders in addition to conventional treatments of NAFLD, such as betaine, L-carnitine, vitamin B complex, and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Betaine and L-carnitine are very promising (as shown by clinical and laboratory evidence of disease improvement) because of widespread impact (as shown by specific biomolecular mechanisms of action) these supplements have on preventing and reversing multiple dysfunctional pathways in pathogenesis of NAFLD.

Betaine

Betaine is a neutral chemical compound that has both anionic and cationic functional groups. It is obtained through the diet or via choline oxidation, and functions as a methyl donor to increase the efficiency of biochemical processes (Lever 2010). It has been utilized therapeutically in diabetes, metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia and liver disease. The value of betaine in liver disease, (NAFLD specifically) is derived from its ability to reverse impaired sulphur related amino acid metabolism, oxidative stress and dysfunctional insulin regulation (Kathirvel 2010).

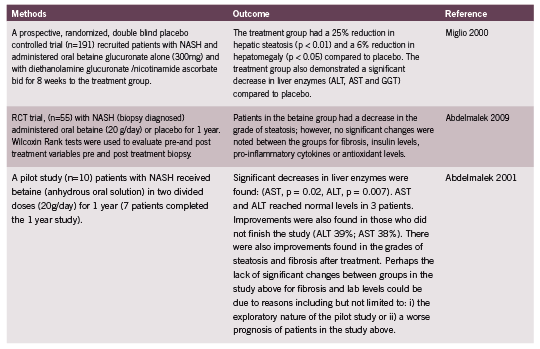

Animal and in-vitro studies have demonstrated that betaine has a preventative and therapeutic role in NAFLD. In one study mice were fed a high-fat diet (20% of calories from fat) for either 7 or 8 months, with added betaine for the last 6 weeks only or without betaine. Mice with high fat diets had increased weight, fasting glucose, insulin, triglyceride levels and hepatic fat content than controls (controls had chow with 9% calories from fat). Betaine treated mice showed a decrease in fasting glucose, insulin, triglyceride levels and hepatic fat content, as well as improved insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis. In vitro experiments furthered these findings and demonstrated that insulin-resistant HepG2 cells had a restoration of insulin receptor substrate phosphorylation and regulation of associated signalling events, such as gluconeogenesis and glycogenesis (Kathirvel 2010). Table 1 summarizes the therapeutic use of betaine in human studies.

L-carnitine

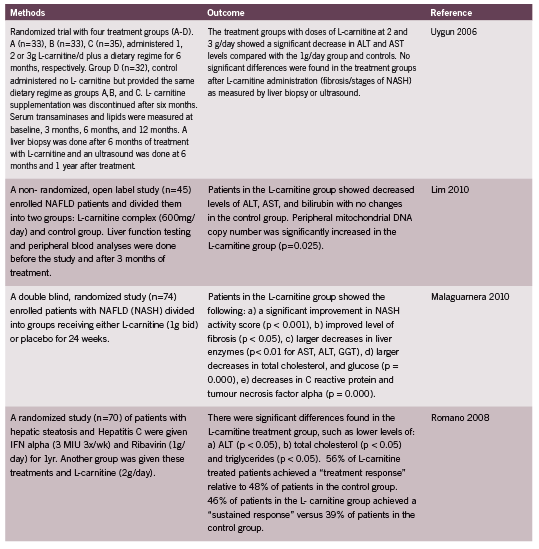

L-carnitine is a compound synthesized from methionine and lysine, and has been therapeutically utilized for cardiovascular disease, Type II Diabetes, osteoporosis, kidney and liver disease. L-carnitine is promising in the treatment of liver disease because it plays a crucial role in liver carnitine palmitoyltransferase-I sensitization, beta oxidation and peroxisome activity (Bremer 1990). It is part of an effective shuttling mechanism that obtains energy through the Kreb’s Cycle via transport of long chain acyl groups into the mitochondrial matrix to form Acetyl-CoA (Olpin 2005). Several animal studies have revealed how L-carnitine improves mitochondrial enzyme function in the liver. One interesting study in rats showcased the effects of L-carnitine in promoting fat utilization and optimal liver enzyme activity: The rats were administered a diet of hydrogenated fat and were kept with or without exercise defined as swimming for 1 hr a day, 6 days/week, for 24 weeks (4 groups of 8 rats per group) or peanut oil diet (4 groups of 8 rats per group), each given L-carnitine or nothing for 24 weeks. The L-carnitine group with the peanut oil diet, as well as exercise showed increased levels of mitochondrial enzymes: NADH dehydrogenase, NADH oxidase and cytochrome C (Karanth 2010). These findings illustrate that L-carnitine functions to increase the activity of carnitine palmitoyl transferase and the oxidative function of hepatocytes by modulating enzymes in the electron transport chain. Table 2 outlines human trials of L-carnitine in NASH.

Conclusions

Non alcoholic fatty liver disease and the more critical presentation of NASH require timely and effective prevention and treatment, given the putative endpoint of cirrhosis and the subclinical nature of the disease in its early stages. Although laboratory parameters were greatly improved after treatment with both betaine and L-carnitine, caution should be exercised in equating lab values to improved clinical effects. Future research should be directed at evaluating whether an additive effect exists with supplementation and conventional therapies. It should be noted that safety of this endeavour would be equivocal at this point.

L-carnitine (dose 500-3000mg) has been safely utilized therapeutically, although an effective dosage for NALFD was shown on average at 2g/day with noted side effects of vomiting, nausea, headache, diarrhea, rhinitis, and evening restlessness (Cruciani 2006). Its therapeutic potential can be attributed to its role as an effective shuttle of fatty acids and its ability to modulate mitochondrial enzymes, thus preserving the integrity of liver tissue. Research has demonstrated that betaine exerts mechanisms that involve modulation of oxidative damage and insulin activity, at a dose of 20g/day in NAFLD with side effects of mild gastrointestinal discomfort.

Although initial intervention requires the introduction of dietary change and exercise alongside first line conventional therapies, Betaine and L-carnitine have demonstrated unique mechanisms of action and excellent laboratory/histological outcomes.

References:

Abdelmalek, MF, Angulo P, Jorgensen RA, Sylvestre PB, Lindor KD. Betaine, a promising new agent for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of a pilot study. Am J Gasteroenterol (2001): 96(9):2711-7.

Abdelmalek, MF, Sanderson SO, Angulo P, Soldevila-Pico C, Liu C, Peter J, Keach J, Cave M, Chen T, McClain CJ, Lindor KD. Betaine for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: results of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology (2009): 50(6):1818-26.

Adams, L and P. Angulo. Treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Postgrad med (2006): 82:315-322.

Angulo, P. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease. NEJM (2002): 346:1221–31.

Bremer, J. The Role of Carnitine in Intracellular Metabolism. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem (1990): 28(5):297-301.

Cruciani, RA, Dvorkin E, Homel P, Malamud S, Culliney B, Lapin J, Portenoy RK, Esteban-Cruciani N. Safety, tolerability and symptom outcomes associated with L-carnitine supplementation in patients with cancer, fatigue, and carnitine deficiency: a phase I/II study. J Pain Symptom Manage. (2006): 32(6) 551-9.

Giovanni, M, R. Gambino , M Cassader and G. Pagano. A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials for the Treatment of NAFLD. Hepatology (2010): 52; 79-104.

Karanth, J and Jeevaratnam, K. Effect of carnitine supplementation on mitochondrial enzymes in liver and skeletal muscle of rat after dietary lipid manipulation and physical activity. Indian J Exp Biol (2010): 48(5):503-10.

Kathirvel, E, Morgan K, Nandgiri G, Sandoval BC, Caudill MA, Bottiglieri T, French SW, Morgan TR. Betaine improves nonalcoholic fatty liver and associated hepatic insulin resistance: a potential mechanism for hepatoprotection by betaine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol (2010): 1068-1077.

Lever, M. and S. Slow. The clinical significance of betaine, an osmolyte with a key role in methyl group metabolism. Clin Biochem (2010): 43(9):732-44.

Lim, CY, Jun DW, Jang SS, Cho WK, Chae JD, Jun JH. Effects of carnitine on peripheral blood mitochondrial DNA copy number and liver function in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Korean J Gasteroenterol (2010): 55(6):384-9.

Malaguarnera, M, Gargante MP, Russo C, Antic T, Vacante M, Malaguarnera M, Avitabile T, Li Volti G, Galvano F. L-carnitine supplementation to diet: a new tool in treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis–a randomized and controlled clinical trial. Am J Gasteroenterol (2010): 1338-45.

Miglio, F, Rovati LC, Santoro A, Setnikar I. Efficacy and safety of oral betaine glucuronate in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. A double-blind, randomized, parallelgroup, placebo-controlled prospective clinical study. Arzneimittelforschung (2000): 50 (8) 722-7.

Olpin, S. Fatty acid oxidation defects as a cause of neuromyopathic disease in infants and adults. Clin Lab (2005): (5-6): 289–306.

Rahn, S. The Gastrointestinal System authors), Academy of Life Underwriting (mixed. Intermediate Medical Life Insurance Underwriting. New York: Academy of Life Insurance Underwriting, 2010. 1-31.

Raszeja-Wyszomirska, J, Lawniczak M, Marlicz W, Miezyńska-Kurtycz J, Milkiewicz P. Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease- New View. Pol Merkur Lekarski (2008): (144) 568-571.

Romano, M, Vacante M, Cristaldi E, Colonna V, Gargante MP, Cammalleri L, Malaguarnera M. L-carnitine treatment reduces steatosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C treated with alpha-interferon and ribavirin. Dig Dis Sci (2008): 53 (4) 1114-21.

Uygun, Ahmet, Kadayıfcı Abdurrahman, Bağcı Sait, Erdil Ahmet, Deveci Salih, Saka Mendane, Yüksel Ateş, Bulucu Fatih, Karaeren Necmettin, Dağalp Kemal. L Carnitine Therapy in Non Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. The Turkish Journal Of Gastroenterology (2000): 196-201.

Wedemeyer, H and Michael Manns. Medscape News. 2003. 04 04 2011 <http://www. medscape.com/viewarticle/458509_2>.

Wedro, Benjamin. www.emedicine.com. 25 Sep 2009. 15 Apr 2011 <http://www. emedicinehealth.com/fatty_liver_disease/page12>. Younossi, ZM. Review article: current management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther (2008): (1):2-12.