Low Back Pain and Pelvic Girdle Pain in PREGNANCY

Assessment and management

Abstract

Low back pain (LBP) and pelvic girdle pain (PGP) associated with pregnancy are common problems that may be under-reported and under-treated. ese conditions have a signi cant impact on activities of daily living and may lead to chronic pain postpartum. While the exact etiology of LBP and PGP in pregnancy is not known, a combination of traumatic, hormonal and biomechanical mechanisms likely contribute to decreased integrity and stability in the back/pelvis during pregnancy. LBP and PGP can be di erentiated based on the location of pain; speci c pain provocation testing can be useful in the diagnosis of PGP. Exercise and acupuncture have been shown to reduce pain, improve functional ability and decrease disability in those with LBP and PGP associated with pregnancy; there is also some evidence for the use of spinal manipulative therapy and pelvic belts.

Half to two-thirds of women experience pregnancy related low back pain (PLBP) and/or pregnancy related pelvic girdle pain (PPGP) (Skaggs 2007, Wu 2004) yet it often goes unreported and untreated, perhaps because there is an assumption that it is a “normal” part of pregnancy. A recent survey found that only 32% of women with PLBP reported their pain to their prenatal care giver and only 25% of prenatal care providers recommended treatment (Wang 2004).

PLBP and PPGP have been correlated with disturbances to daily activities such as standing for 30 minutes, sleep disturbances, and use of pain medication (Mens 1996, Skaggs 2007, Wang 2004). It is therefore important for primary care practitioners to be knowledgeable and able to recommend effective treatment options.

Assessment and Diagnosis

Typically, PLBP is concentrated in the lumbar spine region, whereas PPGP is concentrated between the posterior iliac crests and gluteal fold, particularly in the region of the sacroiliac joint; this can occur in conjunction with or separately from pain in the symphysis (Vleeming 2008). Women are more likely to experience PLBP and PPGP if they have a history of previous low back pain (LBP), history of PLBP and PPGP, and strenuous work (Wu 2004).

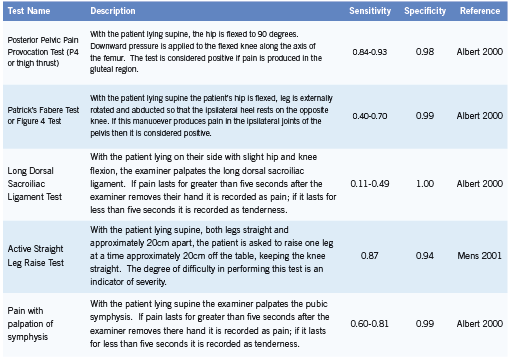

PPGP is diagnosed after other lumbar causes for the pain have been ruled out and when the pain is reproduced by specific clinical tests (Vleeming 2008). Pain provocation tests (Table 1) are useful in assessment and diagnosis of PPGP (Ronchetti 2008, Vleeming 2008).

Other serious causes of PLBP and PPGP must be ruled out with a thorough history and physical examination; differential diagnoses may include osteomyelitis, cauda equina syndrome, disc herniation, urinary tract infection, femoral vein thrombosis, or an obstetric complication.

Prognosis

Typically PPGP resolves within a few weeks to months after delivery but 8-10% of women continue to have pain for one to two years postpartum (Albert 2001, Rost 2006).While PLBP and PPGP are two separate clinical conditions, they can also occur in combination. Women who experience combined PLBP and PPGP appear more likely to experience LBP and pelvic girdle pain (PGP) during the post-partum period than those who experience just PLBP or PPGP (Gutke 2008, Turgut 1998). It is important to recognize that many non-pregnant women with chronic back pain identify pregnancy as the initial onset of their back pain (Mens 1996).

Etiology

The exact etiology of PLBP and PPGP is not clear and may in fact be multi-factorial.

Relaxin is a hormone that is produced in increased quantities during pregnancy and which leads to increased ligamentous laxity (MacLennan 1991).Women with PLBP and PPGP have been shown to have increased motion in their pelvic joints compared to healthy controls (Mens 2009). Smaller and flatter sacroiliac joints predicts an elevated risk of PLBP and PPGP; it has been hypothesized that as a result the loosening of the ligaments during pregnancy this joint becomes less stable (Vleeming 1990). Pain may result from increased shear forces across the sacroiliac joints.

Pregnancy also induces postural and biomechanical changes which could affect the stability of the lumbar spine and pelvis, thereby leading to pain. Increased abdominal muscle length (Fast 1990, Gilleard 1996) and altered angle of insertion have been noted for the rectus abdominus (RA) and have been correlated with the inability to stabilize the pelvis against resistance (Gilleard 1996). Studies using ultrasound have identified increased cross-sectional area of the RA and decreased RA thickness following delivery and in comparison to nulliparous controls (Coldron 2008, Weiss 2009). Sihvonen (1998) also found that changes to the functioning of back extensor muscles were related to back pain in pregnancy. It is possible that changes to the morphology of these muscles could reduce their ability to stabilize the spine and pelvis. Other contributing factors may include altered posture, muscle fatigue, muscle imbalance and previous trauma (Kristiansson 1996, Mens 1996, Perkins 1998).

Conservative Management Prevention

There is some evidence that exercise may play a role in preventing PLBP and PPGP (Mogren 2005, Mørkved 2007). A retrospective study by Mogren (2005) found that a higher number of years of regular leisure physical activity was associated with decreased risk of low back and pelvic pain during pregnancy (p=0.010).

A randomized control trial comparing a 12-week preventative exercise training program to usual care demonstrated positive results in a nulliparous pregnant population (Mørkved 2007). At 36 weeks gestation women in the training group were significantly less likely to report lumbopelvic pain (44% vs 56%; p=0.03) and had significantly higher scores of functional status on Disability Rating Index (DRI) (p=0.01) (Mørkved 2007).

Education

Education as a stand-alone strategy has received little focus for the management of PLBP and PPGP, however many studies include education as a component of a comprehensive program (Elden 2005, Mens 2000, Stuge 2004). Education on relevant anatomy and biomechanics, advice regarding ergonomics of daily activities and reassurance are commonly included and may help to reduce anxiety and fear in women with PLBP and PPGP (Vleeming 2008).

Exercise

In the non-pregnant population alterations to the functioning of the deep abdominal musculature play a role in LBP and exercise programs targeting these muscles appear effective in treating LBP (Ferreira 2010, Hides 2010). Since changes to morphology and functioning of both abdominal and low back musculature have been identified during pregnancy, it is reasonable to consider exercises which target the core musculature as a possible treatment during pregnancy.

Interventions including stabilizing exercises have been shown to be effective in reducing pain and improving functional ability in women with PLBP and PPGP (Elden 2005, Kluge 2011, Stuge 2004). Kluge (2011) compared pain intensity and functional ability in pregnant women before and after either specific stabilizing exercise program or control intervention. Pain intensity decreased in the intervention group from 30.0 to 18.5 (p<0.01); there was also a significant difference in pain intensity between the two groups following the intervention (18.5 compared to 33.0; p<0.01).

The sitting pelvic tilt exercise has been found to be an effective treatment in the third trimester (Suputtitada 2002). Compared to a control group, those performing the exercise had significantly lower pain intensities as measured by visual analogue scale (VAS) after 56 days of performing the exercise (p<0.05) (Suputtitada 2002).

Stuge (2004a) studied the role of exercise in treating PLBP and PPGP during the postpartum period. Physical therapy including ergonomics, massage, joint mobilization, manipulation, electrotherapy, and hot packs was compared to physical therapy plus exercises targeting the core musculature over a 20 week period. Exercise plus physical therapy resulted in statistically and clinically significant lower back pain intensity both in the morning (VAS; p=0.001) and evening (VAS; p<0.001) and lower disability as measured by Oswestry Disability Index (p<0.001) ) compared to those receiving physical therapy only. Differences between groups remained at one and two years postpartum (Stuge 2004b).

In a prospective trial pregnant women were randomized to watergymnastics or a control group; subjects in the water-gymnastics group participated in a once-weekly program for approximately 17-20 weeks. Significantly more women in the control group (17) versus water-gymnastics group (seven) were on sick-leave for back/ LBP after week 32-33 (p=0.031) (Kihlstrand 1999).

Overall exercise targeting the muscles that stabilize the back and pelvis and water gymnastics appear to be effective treatment options, however a few studies have found inconsistent results (Mens 2000, Nilsson-Wikmar 2005).

Spinal Manipulative Therapy

Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) is an effective treatment for low back pain in the non-pregnant population (van Tulder 2006). While SMT may be effective for treating PLBP and PPGP, most studies in pregnant populations have combined SMT with other interventions such as exercise and myofascial release making it difficult to determine the effect of individual treatment modalities (Lisi 2006, Skaggs 2005, Stuge 2004).

For example, Skaggs (2005) applied a multimodal treatment protocol including education, soft tissue mobilization, joint mobilization and manipulation and specific stabilization exercise to 170 patients. Patients were evaluated on the first and second visit using the Bournemouth Questionnaire; the average score on the first visit was 45 (SD=23) and second visit was 34 (SD=22). The difference in scores indicated significant improvement (p<0.01).

Retrospective case series have demonstrated that pregnant women with PLBP who underwent chiropractic care (including SMT) had clinically important improvement on Numerical Rating Scale pain score (Lisi 2005) and reported relief (Diakow 1991).

Acupuncture

Elden (2005) found acupuncture to be superior to standard treatment including information, advice, pelvic belt, and home exercise program targeted to abdominal and gluteal muscles. Following six weeks of twice per week acupuncture, the acupuncture and standard treatment groups differed in pain intensity in the morning (p<0.001) and in the evening (p<0.001) as measured on VAS (Elden 2005). Similar results were also found by Kvorning (2004).

Guerreiro da Silva (2004) compared conventional treatment (pharmacotherapy: paracetamol and hyoscine) to conventional treatment plus acupuncture. Women in the acupuncture group showed a greater reduction in average pain on a numerical rating scale 0-10 (-4.8 points) compared to the control group (-0.3 points; p<0.0001). In addition, use of paracetamol decreased more in the acupuncture group (2.0) versus the control group (0.0; p=0.005).

Pelvic Belts

There is some evidence that pelvic belts help stabilize the pelvis and may be useful in the diagnosis and treatment of PLBP and PPGP. Mens et al (2002) found that pelvic belts significantly decreased sacroiliac joint laxity (p<0.001) and are more effective when positioned directly below the anterior superior iliac spine rather than at the level of symphysis pubis (p=0.006). Use of a pelvic belt has also been correlated with decreased score on the active straight leg test (Mens 2006). Another study by Carr (2003) found a lumbrosacral orthosis to be helpful in reducing pain intensity and effect of pain on daily activities during pregnancy. Pelvic belts are often used in combination with other interventions as part of a comprehensive treatment program.

Other

Other non-conservative treatment options may include pharmacotherapy, prolotherapy, surgery and injection therapy, but are beyond the scope of this paper.

Conclusion

PLBP and PPGP are common problems which significantly impact the activities of daily living in pregnant women. While the etiology is not clear, and may in fact be multi-factorial, the ability to stabilize the lumbar spine and pelvis appears compromised during pregnancy. Exercise and acupuncture are effective conservative treatment options; education, pelvic belts, and spinal manipulative therapy also appear to be useful. Health care providers working with this population should educate patients and consider recommending conservative treatment options.

References

Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Prognosis in four syndromes of pregnancyrelated pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001; 80: 505-511.

Albert H, Godskesen M, Westergaard J. Evaluation of clinical tests used in classification procedures in pregnancy-related pelvic joint pain. Eur Spine J. 2000; 9: 161-166.

Carr CA. Use of a maternity support binder for relief of pregnancy-related back pain. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs.2003; 32: 495-502.

Coldron Y, Stokes M, Newham D, Cook K. Postpartum characteristics of rectus abdominus on ultrasound imaging. Manual Therapy.2008; 13: 112-121.

Diakow RP, Gadsby TA, Gadsby JB, Gleddie JG, Leprich DJ, Scales AM. Back pain during pregnancy and labor. J Manipulative PhysiolTher.1991; 14: 116-18.

Elden H, Ladfors L, Olsen M, Ostgaard H, Hagberg H. Effects of acupuncture and stabilizing exercises as adjunct to standard treatment in pregnancy women with pelvic girdle pain: randomised single blind controlled trial. BMJ.2005; 330: 761-766.

Fast A, Weiss L, Ducommun E, Medina E, Butler J. Low-back pain in pregnancy. Abdominal muscles, sit-up performance and back pain. Spine. 1990; 15(1): 28-30.

Ferriera P, Ferriera M, Maher C, Refshauge K, Herbert R, Hodges P. Changes in recruitment of transverses abdominis correlate with disability in people with chronic low back pain. Br J Sports Med. 2010; 44 (16): 1166-72.

Gilleard WL, Brown JMM. Structure and function of the abdominal muscles in primigravid subjects during pregnancy and the immediate postbirth period. Physical Therapy.1996; 76: 750-762.

Guerreiro da Salva JB, Nakamura MU, Cordeiro JA, Kulay L Jr. Acupuncture for low back pain in pregnancy- a prospective, quasi-randomised, controlled study. Acupunct Med. 2004; 22(2): 60-7.

Gutke, A, Ostgaard H, Oberg B. Predicting persistent pregnancy-related low back pain. Spine. 2008; 33: E386-E393.

Hides JA, Stanton WR, Wilson SJ, Freke M, MeMahon S, Sims K. Retraining motor control of abdominal muscles among elite cricketers with low back pain. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010; 20(6): 834-42.

Kihlstrand M, Stenman B, Nilsson S, Axelsson O. Water-gymnastics reduced the intensity of back/low back pain in pregnancy women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand.1999; 78: 180-185.

Kluge J, Hall D, Louw Q, Theron G, Grové D. Specific exercises to treat pregnancyrelated low back pain in a South African population. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011; 113(3): 187-91.

Kristiansson P, Savardsudd K, von Schoultz B. Back pain during pregnancy. A prospective study. Spine.1996; 21: 1363-1370.

Kvorning N, Holmberg C, Grennert L, Aberg A, Akeson J. Acupuncture relieves pelvic and low-back pain in late pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004; 83(3): 246-50.

Lisi AJ. Chiropractic spinal manipulation for low back pain of pregnancy: a retrospective case series. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2006; 51: e7-e10.

MacLennan AH. The role of the hormone relaxin in human reproduction and pelvic girdle relaxation. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1991; 88: 7-15.

Mens JMA, Pool-Goudzwaard A, Stam HJ. Mobility of the Pelvic Joints in Pregnancy-Related Lumbopelvic Pain. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009; 64: 200-208.

Mens JMA, Damen L, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. The mechanical effect of a pelvic belt in patients with pregnancy-related pelvic pain. Clin Biomech. 2006; 21(2): 122-127.

Mens, JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Koes BW, Stam HJ. Reliability and validity of the active straight leg raise test in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine. 2001; 26(10): 1167-71.

Mens JM, Snijders CJ, Stam HJ. Diagonal trunk muscle exercises in peripartum pelvic pain: a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther. 2000; 80: 1164-1173.

Mens, JMA, Vleeming MB, Stoeckart T, Stan HJ, Snijders CJ. Understanding peripartum pelvic pain. Implications of a patient survey. Spine. 1996; 21: 1363-1370.

Mogren IM. Previous physical activity decreases the risk of low back pain and pelvic pain during pregnancy. Scand J Public Health. 2005; 33: 300-306.

Mørkved S, Salvesen KA, Schei B, Lydersen S, Bø K. Does group training during pregnancy prevent lumbopelvic pain? A randomized clinical trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007; 86: 276-282.

Nilsson-Wikmar L, Holm K, Oijerstedt R, Harms-Ringdahl K. Effect of three different physical therapy treatments on pain and activity in pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain: a randomized clinical trial with 3, 6 and 12 months follow-up postpartum. Spine.2005; 30: 850-856.

Perkins J, Hammer R, Loubert P. Identification and management of pregnancyrelated low back pain. J Nurse Midwifery. 1998; 43(5): 331-339.

Ronchetti I, Vleeming A, van Wingerden J. Physical characteristics of women with severe pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy. A descriptive cohort study. Spine 2008. 33: E145-151.

Rost CC, Jacqueline J, Kaiser A, Verhagen AP, Koes BW. Prognosis of women with pelvic pain during pregnancy: a long-term follow-up study. Acta Ostet Gynecol Scand. 2006; 85: 771-777.

Sihvonen T, Huttunen M, Makkonen M, Airaksinen O. Functional Changes in Back Muscle Activity Correlate With Pain Intensity and Prediction of Low Back Pain During Pregnancy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.1998; 79: 1210-2.

Skaggs C, Prather H, Gross G, George J, Thompson P, Nelson D. Back and pelvic pain in an underserved United States pregnancy population: A preliminary descriptive survey. J Manipulative PhysiolTher. 2007; 30: 130-134.

Skaggs CD, Gross G, Ducar D, Thompson PA, Nelson DM. A comprehensive musculoskeletal management program reduces pain and disability in pregnancy. J Chiropr Educ. 2005; 19: 31-2. (abstr)

Stuge B, Laerum E, Kirkesola G, Vøllestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy. Spine 2004a; 29: 351-359.

Stuge B, Veierød MB, Laerum E, Vøllestad N. The efficacy of a treatment program focusing on specific stabilizing exercises for pelvic girdle pain after pregnancy: a twoyear follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Spine. 2004b; 29(10): E197-203.

Suputtitada A, Wacharapreechanont T, Chaisayan P. Effect of the “sitting pelvic tilt exercise” during the third trimester in primigravidas on back pain. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002; 85 Suppl 1: S170-9.

Turgut F, Turgut M, Cetinsahin M. A prospective study of persistent back pain after pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998; 80: 45-48.

Vleeming A, Albert H, Östgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. Eur Spine J. 2008; 17: 794-819.

Vleeming A, Stoeckart R, Volkers AC, Snijders CJ. Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part I. Clinical anatomical aspects.Spine.1990; 15: 130-132.

Van Tulder R, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, del Real MT, Hutchinson A, Koes B, Malmivaara A. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006; 15 Suppl 2: S169-91.

Wang SM, Dezinno P, Maranets I, Berman MR, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Kain ZN. Low back pain during pregnancy: prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Jul; 104(1): 65-70.

Weiss C, Triano J, Campbell M, Croy M. Abdominal muscle thickness in postpartum vs. nulliparous women: A preliminary study. J of Chiropr Educ. 2009; 23(1): 100. (abstr)

Wu H, Meijer O, Uegaki K, Mens J, van Dieen J, Wuisman P, Ostgaard H. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP)I: Terminology, clinical presentation and prevalence. Eur Spine J. 2004; 13: 575-589.