Exercise rehabilitation for cancer patients

Basis and anticipated impact

Introduction

Chronic diseases are the most serious public health burden in Canada and the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. In Canada, about two-thirds of total deaths are due to chronic diseases; about 16 million Canadians live with a chronic disease (Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada 2011). ese people are often at risk for several comorbidities because of the similarity in underlying risk factors. Physical inactivity is one lifestyle risk factor for many of these diseases and, at the same time, it is routinely prescribed in the rehabilitation for these diseases. Exercise (a form of physical activity that is deliberate and performed repeatedly over a period of time) has consistently been used in the prevention, treatment and rehabilitation of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, musculoskeletal disease, hypertension, neuropsychiatric diseases, respiratory diseases, and now, cancer (Durstines 2009).

Convincing evidence supports the role for exercise across the cancer spectrum. e continuum includes exercise as prevention, during treatment, recovery, living after recovery and for some, living with advanced cancer (Doyle 2009). Evidence will be reviewed to support the role that exercise plays when utilized in conjunction with conventional therapies and health promotion strategies during and post-cancer treatment. It is important to note that survival rates have increased in Canada such that the fi ve- year survival for all cancers combined is 62% and can be as high as 90% for thyroid, prostate and testicular cancers (Canadian Cancer Society 2011). A combination of risk factor identifi cation and screening, early detection, advances in detection methods and treatment therapies all improve survival. With these improvements, more patients with cancer are living longer, and hence, require long-term management. is fact prompted the early research into strategies to help improve the quality of life for cancer survivors; exercise prescription being one strategy.

Cancer and Exercise

Cancer is a disease that has touched almost everyone’s life either personally or through family or friends and its eff ects are far-reaching. It is a term for diseases in which abnormal cells divide without control and can invade nearby tissues (National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health 2010). Treatment, consisting of some combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and/or immunotherapy may eradicate the tumor but often leaves individuals struggling to regain the quality of life they once had before cancer diagnosis. e eff ects of treatment can and do cause physiological alterations to normal tissue and body functions. Immune, cardiovascular, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, hepatic, neuroendocrine, and dermatological toxicity result in varying types and degrees of symptoms (Schneider 2003). Side eff ects include, but are not limited to, fatigue, lymphedema, pain, fat gain, muscle atrophy, sleep disturbance, depression, peripheral neuropathy, cognitive decline, bone loss, anemia, impaired immune function and secondary cancers (Schmitz 2011).

It became clear that the positive eff ects of exercise were opposite these negative side eff ects of treatment. Going back to the early work of Winningham (1991), where a walking program for people with cancer was used to counter the debilitating eff ects of disease, treatment and inactivity (Winningham 1991), several research reports emerged indicating that physical activity and/or exercise may be useful for improving the quality of life of cancer survivors. In addition to giving cancer survivors some control over their own lives, exercise also provides physiological adaptations that contribute to reduced side eff ects.

The type of exercise training (aerobic, resistance or both), the patient population (single cancer type or a mixed group of cancer type) and the fact that treatment protocols are not consistent from person to person, have made it difficult to conduct randomized control studies for each group or condition under varying exercise training modes, duration and intensity, with the intent of providing specific exercise guidelines. Progress has been made for groups such as breast, prostate, colorectal, and hematological cancers. Synthesized evidence-based research (Doyle 2009), a systematic review and meta-analysis (Speck 2010) and a Roundtable consensus paper (Schmitz 2011) collectively demonstrate that exercise is safe and feasible during cancer treatment and results in:

• improvement in the quality of life during and after treatment

• improvement in functional capacity as measured by aerobic fitness scores and muscular strength

• no increased onset of lymphedema associated with breast cancer

• improvements in body composition favoring increased lean tissue and/or reduced body fat

• protection from loss of bone mineral density

• reduction in cancer related fatigue

• reduction in sleep disturbances • improvements in mood states and self-esteem, reduced anxiety and depression

Throughout and beyond the treatment phase, exercise is important. There were reductions in secondary cancers and mortality rates with increased levels of physical activity in 832 patients with stage III colon cancer (Meyerhardt 2006). In a study of 5,204 participants in the Nurse’s Health Study, weight and weight gain were positively associated with higher rates of breast cancer recurrence and mortality (Kroenke 2005). Exercise has been proposed as one mechanism to prevent this. Additional concerns of cardiac and pulmonary toxicities from cancer therapy are now being documented and addressed (Carver 2007) and these patients would benefit from exercise interventions early in their treatment phase that continue post treatment.

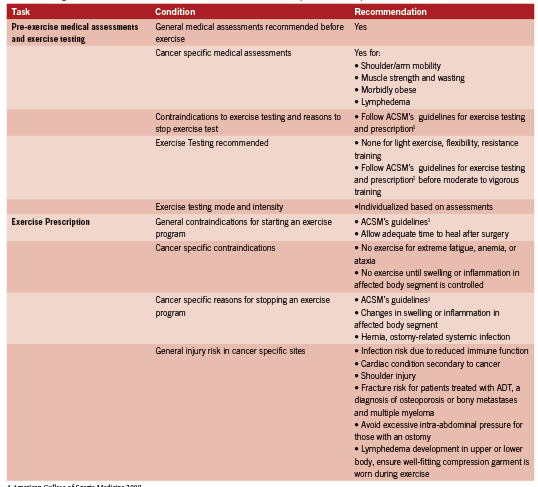

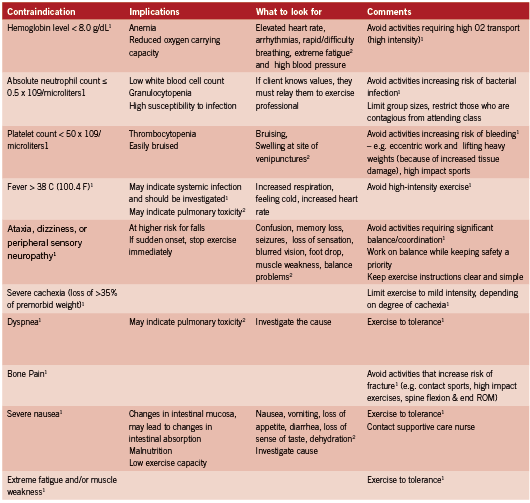

Cancer Specific Guidelines

Given the current interest in cancer and exercise, a roundtable was convened by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) to develop new recommendations for exercise training both during and after cancer treatment. With the release of the ACSM guidelines in 2010, it is recommended that cancer patients and survivors “avoid inactivity”, and “return to or achieve 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise plus resistance and flexibility exercises” (Schmitz 2011) . In this guideline, specific information is provided on medical and exercise assessment, and exercise management with particular emphasis on specific disease site recommendations and contraindications. Table 1 is a condensed version of these guidelines while Table 2 highlights specific contraindications and suggests indications and strategies to minimize risk.

The evidence is compelling that exercise may reduce side effects of cancer treatment, improve psychological and physiological wellness and increase survivorship. There is a need for accessible programs and exercise professionals to provide the appropriate exercise suited to the unique needs of cancer survivors. The recently released ACSM Cancer Exercise Trainer certification and the publication of the exercise guidelines will increase the capacity of fitness professionals to serve the needs of cancer survivors. Fitness professionals who train cancer survivors need to design exercise programs to meet individual needs, taking into consideration their medical history (specific diagnosis & treatment), side effects and limitations, comorbidities, activity level and of course, readiness to engage in an exercise program. Further support for exercise in disease prevention and treatment comes from a recent ACSM initiative called Exercise is Medicine ™. Their vision is “to make physical activity and exercise a standard part of a global disease prevention and treatment medical paradigm” (Exercise is Medicine 2011).

The Canadian Experience

The Oncology Rehabilitation Program at the Ottawa Regional Cancer Centre was the first in Canada to describe a safe and effective exercise intervention program showing that patients (N=261) with a variety of cancers at various stages of illness can safely participate in a program of structured physical activity with no adverse events (Segal1999). Significant contributions to our understanding of the role exercise plays in cancer management come from research-based programs of Dr. Courneya at the University of Alberta, culminating in the development of the ACSM cancer guidelines (Courneya 2000, Courneya 2001, Courneya 2007).

Developed at the University of Waterloo, UW WELL-FIT is an exercise based program for patients in treatment for cancer. After 10 years, the UW WELL-FIT program has demonstrated results similar to Segal (1999). After a 12 week exercise intervention program, cardiovascular assessments were performed on 305 (78.4%) participants with significant improvements in physical function This was demonstrated by decreases in heart rate, systolic blood pressure and RPE at the submaximal level (p<.01) and an increase in maximal workrate attained. The summary component scales of the SF-36 (physical and mental) were significantly improved as well as all eight sub-scales (p<.01) indicating an improved quality of life (Noble in press). Additionally, UW WELL-FIT provided a framework to design and implement exercise rehabilitation programs (Russell 2009), which has been made available as a resource for health professionals wanting to start an oncology rehabilitation exercisebased program (http://uwfitness.uwaterloo.ca/).

The task now is to initiate and promote programs that ensure access for all cancer patients undergoing treatment. It is time to increase awareness for oncologists and allied health professionals of the new ACSM guidelines and their importance, and to provide trained exercise professionals to manage these programs. It is equally important to educate patients about their need to exercise during treatment and beyond, and to seek out opportunities that will fulfill their exercise needs.

References:

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Execise Testing and Prescription 8th Edition. Philadelphia: Lippeincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009.

Canadian Cancer Society. (2011, May 18). Retrieved 06 06, 2011, from http:// www. cancer.ca /Canada-wide /About%20us /Media%20centre /CW-Media%20releases/CW- 2011/ Backgrounder %20Canadian %20Cancer %20Statistics %20at %20a%20 glance. aspx?sc_lang=en

Carver JR, Shapiro CL, Ng A, Jacobs L, Schwartz C, Virgo KS, Hagerty KL, Somerfield MR, Vaughn DJ; ASCO Cancer Survivorship Expert Panel. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical evidence review on the ongoing care of adult cancer survivors: cardiac and pulmonary late effects. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Sep 1;25(25):3991-4008.

Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada. (2011). Retrieved May 17, 2011, from http://www.cdpac.ca/content.php?doc=1.

Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Jones LW. Coping with cancer: can exercise help? Phys Sportsmed. 2000 May;28(5):49-73.

Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Framework PEACE: an organizational model for examining physical exercise across the cancer experience. Ann Behav Med. 2001 Fall;23(4):263-72.

Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and cancer control. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007 Nov;23(4):242-52.

Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Grant B, McTiernan A, Rock CL, Thompson C, Gansler T, Andrews KS; 2006 Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer Survivorship Advisory Committee; American Cancer Society. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006 Nov- Dec;56(6):323-53.

Durstines JL, Moore GE, Painter P, and Roberts S. ACSM’s Exercise Management for Persons with Chronic Diseases and Diabilities. Champlaign IL: Human Kinetics. 2009.

Exercise is Medicine. Your Prescription for Health Series. Retrieved June 12, 2011. http://exerciseismedicine.org/documents/YPH_Cancer.pdf.

Kroenke CH, Chen WY, Rosner B, Holmes MD. Weight, weight gain, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Mar 1;23(7):1370-8.

Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Thomas J, Nelson H, Whittom R, Hantel A, Schilsky RL, Fuchs CS. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Aug 1;24(22):3535-41.

National Cancer Institute at the National Institues of Health. (2010, December 7). Retrieved June 10, 2011, from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/cancerlibrary/ what-is-cancer

Noble M, Russell C,Kraemer L,Sharratt M. UW WELL-FIT: The impact of supervised exercise programs on physical capacity and quality of life in individuals receiving treatment for cancer.Supportive Care in Cancer. In Press.

Russell C, Kraemer L, Noble M, Sharratt M. Active Living for Older Adults in Treatment for Cancer: Framework for Design. Orangeville Ontario: Active Living Coalition For Older Adults http://www.alcoa.ca/e/cancer_project/index.htm. 2009.

Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM,Irwin ML, Wolin KY, Segal RJ, Lucia A, Schneider CM, von Gruenigen VE, Schwartz AL; American College of Sports Medicine. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010 Jul;42(7):1409-26.

Schneider CM, Dennehy CA, and Carter SD. Exercise and Cancer Recovery. Champaign, IL United States: Human Kinetics. 2003.

Segal R, Evans W, Johnson D, Smith J, Colletta SP, Corsini L, Reid R. Oncology Rehabilitation Program at the Ottawa Regional Cancer Centre: program description. CMAJ. 1999 Aug 10;161(3):282-5.

Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010 Jun;4(2):87-100.

Winningham ML. Walking program for people with cancer. Getting started. Cancer Nurs. 1991 Oct;14(5):270-6.