DHEA Part II

Autoimmunity and Bone Health

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is a weak androgen secreted from the adrenal cortex, and an immunologically active hormone. DHEA supplementation has been shown to improve bone density and metabolism in several patient populations, including the elderly, as well as patients with lupus or anorexia. DHEA has also been shown to improve measures of disease activity in patients with lupus and inflammatory bowel disease, and may have the ability to reduce steroid medication requirements. In the contexts of bone health and autoimmunity, dosing of DHEA ranges from 50-200mg daily. Adverse effects appear to be limited to acne and hirsutism in women. This paper reviews findings from nine human trials of DHEA for bone health and nine human trials of DHEA in patients with autoimmune disease.

Introduction

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and its sulphated precursor DHEA-S, is a weak adrenal androgen and the most abundant steroid hormone in the body (Andus 2003). Circulating levels peak during the third decade of life (DHEAS 10μM and DHEA 10nM, slightly lower in women) and decline to approximately 20-30% those levels by the seventh decade of life (Hazeldine 2010). DHEA acts as a precursor for other steroid hormones in the body, including androstenedione, estradiol, and testosterone (Papierska 2012, Weiss 2009), and has been shown to possess immune regulatory and anti-inflammatory effects through various pathways, including inhibition of NF-kappaB activation and inhibition of IL-6 and IL-12 secretion via PPAR-alpha (Andus 2003). DHEA has been shown to inhibit Th2 cytokine secretion associated with asthma in vitro and inhibit bronchial hyperreactivity in vivo (Liou 2011). In older human subjects aged 65-75 years with impaired glucose tolerance, DHEA supplementation (50mg/d) for two years not only improved glucose tolerance but also reduced circulating levels of IL-6 and TNFalpha (Weiss 2011). DHEA has also been shown to offset the thymic involution that occurs with glucocorticoid administration in animals (Hazeldine 2010, May 1990).

Unfortunately, DHEA is currently banned in Canada due to historical abuse by professional athletes. Nonetheless, as this remains a promising therapy for applications in female fertility (reviewed in Part I) as well as bone health and autoimmune disease, we hope that the status of DHEA may be revisited by Health Canada in the future. Prasterone is a proprietary, synthetic form of DHEA that is sold as a prescription drug.

Bone Health

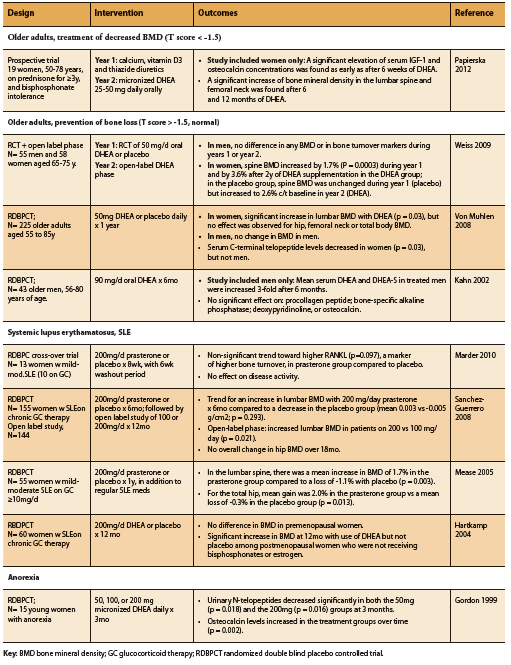

DHEA supplementation has been shown to increase bone mineral density (BMD) among older adults, patients with anorexia, as well as SLE patients on prednisone therapy (Table 1). As might be expected, this effect seems to be most marked among those with pre-existing bone loss as opposed to those with normal BMD at baseline, as well as among women compared to men (Papierska 2012, Von Muhlen 2008, Weiss 2009). In a study of older men and women on prednisone and with osteopenia, supplementation with DHEA resulted in increased serum IGF-1 and osteocalcin alongside increased lumbar and femoral BMD (Papierska 2012). Among elderly patients with normal bone density, however, further benefit on BMD from DHEA supplementation appears to be restricted to women, with no significant BMD increase demonstrated among elderly men with normal BMD (Kahn 2002, Von Muhlen 2008, Weiss 2009). The reason for this gender difference is unclear, but may be related to differential hormone metabolism. Indeed, DHEA supplementation among older adults (25-50mg/d) has been shown to increase serum levels of androstenedione, testosterone, and estradiol particularly in women (Papierska 2012, Von Muhlen 2008, Weiss 2009).

Among patients with SLE, DHEA supplementation has also been shown to significantly improve BMD when compared to placebo (Hartkamp 2004, Mease 2005, Sanchez-Guerrero 2008). A randomized placebo controlled double blind study found that DHEA supplementation was also of benefit among young women with anorexia. A dose of 50mg/d was able to restore physiologic DHEA levels within three months, and dosages between 50-300mg were able to improve markers of bone metabolism including osteocalcin and urinary N-telopeptides (Gordon 1999).

Autoimmune Disease Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

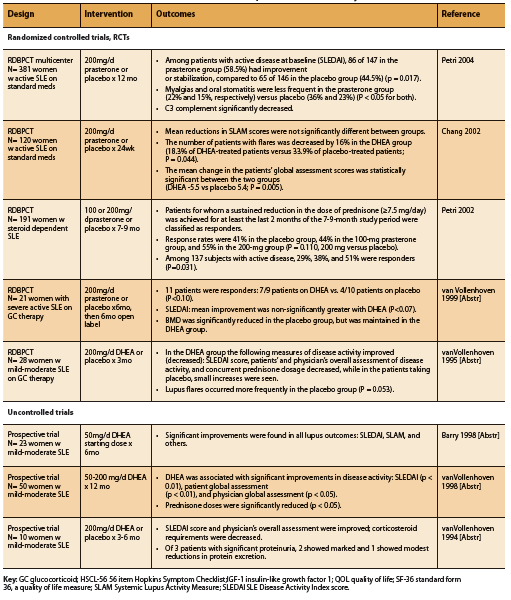

A total of eight human trials, five RCTs and three prospective trials, conducted in patients with SLE report significant improvements in disease activity and/ or corticosteroid requirements associated with supplementation of DHEA at a dosage of 50-200mg daily (See Table 2). The Systemic Lupus Activity Measure (SLAM) and SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) scoring systems were used to assess impact on disease activity.

Four of five RCTs found significant improvements in measures of disease activity, decreased number of disease flares, or reduced prednisone requirements (Chang 2002, Petri 2004, Petri 2002, van Vollenhoven 1995). Two RCTs demonstrated significant improvements in SLEDAI score with DHEA compared to placebo (Petri 2004, van Vollenhoven 1995). An earlier study by Petri et al found that among patients with active, steroiddependent disease, a significantly greater number of DHEA-treated patients were able to sustain a reduction in steroid dose equal to or greater than 7.5mg/d, defined as responders, compared to placebo (P=0.031). Chang et al found that although there was no significant difference in the SLAM score reductions of patients treated with DHEA or placebo, the number of patients with disease flares was significantly lower in the DHEA group (2002). DHEA-treated patients also had significantly better global assessment scores (p= 0.005) and fewer serious adverse events, most of which were related to SLE disease flares (p= 0.010) (Chang 2002).

The only adverse events reported with DHEA dosages between 50-200mg/d were acne and hirsutism (Barry 1998, Petri 2004, 2002, van Vollenhoven 1998, 1995, 1994).

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abnormally lower DHEA/ DHEA-S levels have been described in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, compared to healthy controls (de la Torre 1998, Straub 1998). One study found that among patients with ulcerative colitis, DHEA-S was 1350 nmol/L, and in patients with Crohn’s disease DHEA-S was 1850 nmol/L, while healthy controls had a level almost two-fold higher, 3300 nmol/L (p<0.001 and p<0.01 respectively) (de la Torre 1998).

One prospective trial in patients with chronic, active, refractory IBD found that treatment with 200mg DHEA once daily for approximately two months induced remission in 60% of patients (12 of 20 patients in total; six Crohn’s and six ulcerative colitis) (Andus 2003). Remission was defined as Crohn’s disease activity index <150 or clinical activity index ≤4, which scores eight sign and symptoms of ulcerative colitis, including the number of soft stools; blood in the stools; general wellbeing; abdominal cramps or pain; fever; extraintestinal manifestations; erythrocyte sedimentation rate; and hemoglobin level (Andus 2003).

Subsequent to the publication of this study, the same group of authors published a case report relating the use of DHEA to treat pouchitis (Klebl 2003). A 35-year old women with chronic active pouchitis was treated with 200mg DHEA per day for eight weeks. Her stool frequency dropped from 15-18 per day to eight per day. Eight weeks after her DHEA treatment was discontinued, the numbers of stools increased again to 12-18 per day and her pain returned, indicating that DHEA was likely responsible for her initial improvement, and that ongoing treatment may be required.

Currently, the small number of studies that have examined DHEA supplementation in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis have failed to show benefit (Giltay 1998, Hartkamp 2008, Pillemer 2004, Virkki 2010), however this area deserves further study.

Conclusion

DHEA therapy in the treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis as well as SLE and IBD is supported by human clinical research. Evidence demonstrates that DHEA can increase BMD in the elderly as well as in patients with SLE or anorexia. DHEA may be a disease-modifying agent in patients with SLE and IBD, decreasing disease activity and acting as steroid-sparing agent. Adverse events reported with use of DHEA 50-200mg for up to one year appear to be limited to mild acne and hirsutism. In future it is hoped that this promising agent may once again become available for human therapeutic application in Canada.

References

Andus T, Klebl F, Rogler G, Bregenzer N, Schölmerich J, Straub RH. Patientswith refractory Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis respond todehydroepiandrosterone: a pilot study. Aliment PharmacolTher. 2003Feb;17(3):409-14.

Barry NN, McGuire JL, van Vollenhoven RF. Dehydroepiandrosterone in systemic lupus erythematosus: relationship between dosage, serum levels, and clinical response. J Rheumatol. 1998 Dec;25(12):2352-6.

Chang DM, Lan JL, Lin HY, Luo SF. Dehydroepiandrosterone treatment of women with mild-to-moderate systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Nov;46(11):2924-7.

de la Torre B, Hedman M, Befrits R. Blood and tissue dehydroepiandrosteronesulphate levels and their relationship to chronic inflammatory bowel disease. ClinExpRheumatol. 1998 Sep- Oct;16(5):579-82.

Giltay EJ, van Schaardenburg D, Gooren LJ, von Blomberg BM, Fonk JC, Touw DJ, Dijkmans BA. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone administration on disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.Br J Rheumatol. 1998 Jun;37(6):705-6.

Gordon CM, Grace E, Emans SJ, Goodman E, Crawford MH, Leboff MS. Changes in bone turnover markers and menstrual function after short-term oral DHEA in young women with anorexia nervosa. J Bone Miner Res. 1999 Jan;14(1):136-45.

Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, Bootsma H, Kruize AA, Bijlsma JW, Derksen RH. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone administration on fatigue, well-being, and functioning in women with primary Sjögren syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jan;67(1):91-7.

Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, Bijl M, Bijlsma JW, Derksen RH. The effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on lumbar spine bone mineral density in patients with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Nov;50(11):3591-5.

Hazeldine J, Arlt W, Lord JM. Dehydroepiandrosterone as a regulator of immune cell function. J Steroid BiochemMol Biol. 2010 May 31;120(2-3):127-36.

Kahn AJ, Halloran B, Wolkowitz O, Brizendine L. Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation and bone turnover in middle-aged to elderly men. J ClinEndocrinolMetab. 2002 Apr;87(4):1544-9.

Klebl FH, Bregenzer N, Rogler G, Straub RH, Schölmerich J, Andus T. Treatment of pouchitis with dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) – a case report. Z Gastroenterol. 2003 Nov;41(11):1087-90.

Kocis P. Prasterone. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006 Nov 15;63(22):2201-10.

Liou CJ, Huang WC. Dehydroepiandrosterone suppresses eosinophil infiltration and airway hyperresponsiveness via modulation of chemokines and Th2 cytokines in ovalbumin-sensitized mice. J ClinImmunol. 2011 Aug;31(4):656-65.

Marder W, Somers EC, Kaplan MJ, Anderson MR, Lewis EE, McCune WJ. Effects of prasterone (dehydroepiandrosterone) on markers of cardiovascular risk and bone turnover in premenopausal women with systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot study. Lupus. 2010 Sep;19(10):1229-36.

May M, Holmes E, Rogers W, Poth M. Protection from glucocorticoid induced thymic involution by dehydroepiandrosterone. Life Sci. 1990;46(22):1627-31.

Mease PJ, Ginzler EM, Gluck OS, Schiff M, Goldman A, Greenwald M, Cohen S, Egan R, Quarles BJ, Schwartz KE. Effects of prasterone on bone mineral density in women with systemic lupus erythematosus receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy. J Rheumatol. 2005 Apr;32(4):616-21.

Papierska L, Rabijewski M, Kasperlik-Załuska A, Zgliczyński W. Effect of DHEA supplementation on serum IGF-1, osteocalcin, and bone mineral density in postmenopausal, glucocorticoid-treated women. Adv Med Sci. 2012 Jun 1;57(1):51-7.

Petri MA, Mease PJ, Merrill JT, Lahita RG, Iannini MJ, Yocum DE, Ginzler EM, Katz RS, Gluck OS, Genovese MC, Van Vollenhoven R, Kalunian KC, Manzi S, Greenwald MW, Buyon JP, Olsen NJ, Schiff MH, Kavanaugh AF, Caldwell JR, Ramsey- Goldman R, St Clair EW, Goldman AL, Egan RM, Polisson RP, Moder KG, Rothfield NF, Spencer RT, Hobbs K, Fessler BJ, Calabrese LH, Moreland LW, Cohen SB, Quarles BJ, Strand V, Gurwith M, Schwartz KE. Effects of prasterone on disease activity and symptoms in women with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Sep;50(9):2858-68.

Petri MA, Lahita RG, Van Vollenhoven RF, Merrill JT, Schiff M, Ginzler EM, Strand V, Kunz A, Gorelick KJ, Schwartz KE; GL601 Study Group. Effects of prasterone on corticosteroid requirements of women with systemic lupus erythematosus: a doubleblind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Jul;46(7):1820-9.

Pillemer SR, Brennan MT, Sankar V, Leakan RA, Smith JA, Grisius M, Ligier S, Radfar L, Kok MR, Kingman A, Fox PC. Pilot clinical trial of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) versus placebo for Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Aug 15;51(4):601-4.

Sánchez-Guerrero J, Fragoso-Loyo HE, Neuwelt CM, Wallace DJ, Ginzler EM, Sherrer YR, McIlwain HH, Freeman PG, Aranow C, Petri MA, Deodhar AA, Blanton E, Manzi S, Kavanaugh A, Lisse JR, Ramsey-Goldman R, McKay JD, Kivitz AJ, Mease PJ, Winkler AE, Kahl LE, Lee AH, Furie RA, Strand CV, Lou L, Ahmed M, Quarles B, Schwartz KE. Effects of prasterone on bone mineral density in women with active systemic lupus erythematosus receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy. J Rheumatol. 2008 Aug;35(8):1567-75.

Straub RH, Vogl D, Gross V, Lang B, Schölmerich J, Andus T. Association of humoral markers of inflammation and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate or cortisol serum levels in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998 Nov;93(11):2197-202.

vanVollenhoven RF, Park JL, Genovese MC, West JP, McGuire JL. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of dehydroepiandrosterone in severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1999;8(3):181-7.[Abstr]

vanVollenhoven RF, Morabito LM, Engleman EG, McGuire JL. Treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus with dehydroepiandrosterone: 50 patients treated up to 12 months. J Rheumatol. 1998 Feb;25(2):285-9.[Abstr]

vanVollenhoven RF, Engleman EG, McGuire JL. Dehydroepiandrosterone in systemic lupus erythematosus. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Dec;38(12):1826-31.[Abstr]

vanVollenhoven RF, Engleman EG, McGuire JL. An open study of dehydroepiandrosterone in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 Sep;37(9):1305-10.[Abstr]

Virkki LM, Porola P, Forsblad-d’Elia H, Valtysdottir S, Solovieva SA, Konttinen YT. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) substitution treatment for severe fatigue in DHEA-deficient patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome.Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010 Jan 15;62(1):118-24.

vonMühlen D, Laughlin GA, Kritz-Silverstein D, Bergstrom J, Bettencourt R. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation on bone mineral density, bone markers, and body composition in older adults: the DAWN trial. Osteoporos Int. 2008 May;19(5):699-707.

Weiss EP, Shah K, Fontana L, Lambert CP, Holloszy JO, Villareal DT.Dehydroepiandrosterone replacement therapy in older adults: 1- and 2-y effects on bone. Am J ClinNutr. 2009 May;89(5):1459-67.

Weiss EP, Villareal DT, Fontana L, Han DH, Holloszy JO.Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) replacement decreases insulin resistance and lowers inflammatory cytokines in aging humans. Aging (Albany NY). 2011 May;3(5):533-42